The 28th of May marks the anniversary of the 1926 coup – the second of Portugal’s three twentieth-century revolutions. But, uniquely this one has no public holiday to mark the event. Unlike the others, there are no memorials and no heroes. So what is the story of the forgotten coup?

The 1926 military coup, which began on 28 May, brought to an end Portugal’s First Republic, itself the creation of an earlier coup in 1910, which ended the monarchy. The republic was more democratic than previous regimes, it had a national assembly, regular elections, and a written constitution. Those are normally developments to be celebrated. However, Portugal’s First Republic was a mess.

The government, which became established after the overthrow of the monarchy, agreed on two things: it was against monarchical rule and the Catholic church. The monarchy had been ended in the coup, although a few royalists remained and made various unsuccessful attempts to restore royal rule. The anti-clericalism of the first republic was deep-seated. The government took swift action to end the church’s influence in education, seized large amounts of church property, withdrew citizenship from Jesuits and cancelled most public religious feast day celebrations. So, the monarchy was gone, and the church suppressed. Everyone in the republican government was happy with that. The problem was they agreed on nothing else.

The republic was dominated by the Republican Party, but it was riddled with factions and personal fiefdoms. Aside from what it opposed, there was no core philosophy about what it stood for. The party dominated governments from 1911 right through to the 1926 coup, but it was a shambles. In that period, there were 44 administrations and nine presidents. Some administrations were ended by violence and assassinations, rather than the ballot box. Such chaotic politics meant that few, if any, of the country’s problems were tackled in any way. The economy suffered as a result – revolving governments piled up spending without addressing taxation, and the spiralling deficits caused the currency to plummet and inflation to soar. By 1926, prices were 30 times higher than they had been in 1914. The reputation of the financial system tumbled even further in 1925 when the Bank of Portugal failed to prevent a vast amount of counterfeit banknotes from getting into circulation.

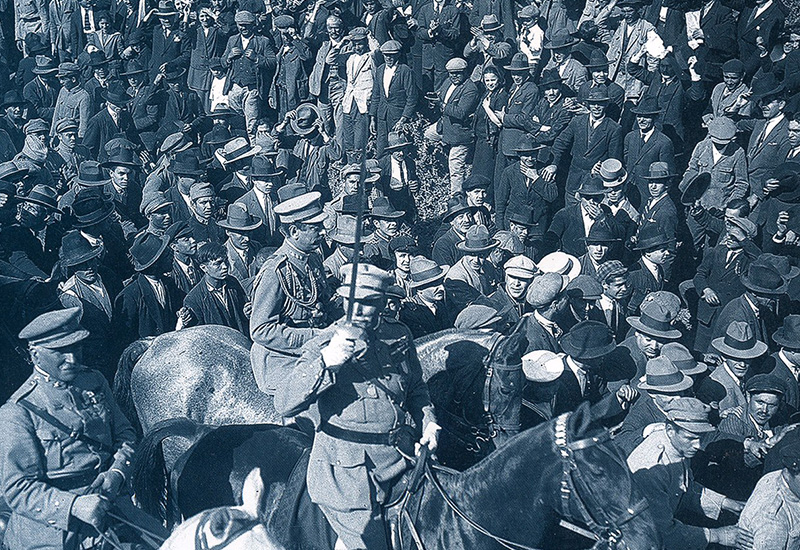

Manuel de Oliveira Gomes da Costa (Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons)

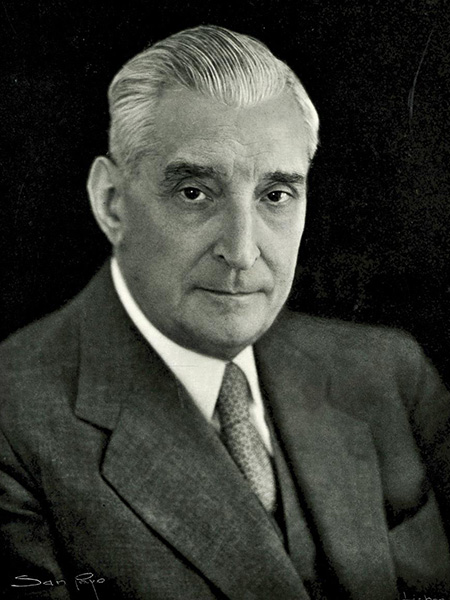

António Óscar de Fragoso Carmona (Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons)

The army – who had been decisive in overthrowing the monarchy – rapidly became disenchanted with what it had ushered in in its place. Dismay at the chaos and corruption of the government was compounded by low pay and poor conditions for soldiers. Unsurprisingly, many in the army concluded that it was time to intervene again, and to put a stop to this failed experiment in republican, democratic government. There were a number of abortive coup attempts after the First World War. But the one that succeeded, in 1926, was led by Manuel Gomes da Costa.

Then a general, this decorated veteran of numerous colonial battles and the First World War assembled 15,000 troops in the centre of Lisbon and marched on the government, which he accused of having an “unforgivable lack of vision”, demanding its resignation. He got it – without any struggle at all. The weak and hopeless government realised that nobody would come to its defence, certainly not the disillusioned public who saw their circumstances deteriorating month by month. It had become the Republic that lacked republicans.

By 3 June, Gomes da Costa had dissolved the Parliament of the old republic and sacked every single municipal chief across the country. By 29 June, he was himself President – the bloodless coup was complete and the First Republic consigned to its ignominious place in history. However, Costa was, in reality, just an expendable figurehead and was himself ousted on 9 July by the ultra-conservative hard-line officer Óscar Carmona. He became the real survivor of the coup, serving as the country’s president until 1951.

A coup like this, which brought to an end a period of shambolic chaos, might then be deserving of a little recognition on its anniversary if not another public holiday. It doesn’t get any of that because of what subsequently emerged.

At the time the military leaders were installing a new government, few amongst the public took note of the new finance minister, António Salazar. But within just a few years, he had become the dominant force in the new government, and went on to found his dictatorship, which even outlived him and survived until the 1974 revolution, which was remembered and celebrated across Portugal last month.

The 1926 coup has no heroes, because its significance came to rest not on what it ended, but on what it began.

James Plaskitt was a Member of Parliament in the UK and served as a minister in Tony Blair’s government. He is now retired in the Algarve.

Main image: Gomes da Costa and his troops after the Revolution of 28 May, 1926 (Joshua Benoliel Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons)