On the 50th anniversary of the Carnation Revolution, an investigation into the days after the political power shifted in the Algarve.

The 25 of April 1974, also known as the Revolução dos Cravos (Carnation Revolution), is a public holiday in Portugal that celebrates the day when the dictatorial fascist regime known as Estado Novo was overthrown. The Movimento das Forças Armadas (MFA) carried out the military coup. The uprising occurred in Lisbon and was undertaken with almost no violence or bloodshed.

The Carnation Revolution got its name from the carnations placed in the muzzles of guns and on the soldiers’ uniforms, which were given to them by the crowds. A combination of factors led to the uprising: discontent with the Portuguese colonial war in Africa, a lack of freedom and rights, and concerns about Portugal’s slow development.

Before 25 April 1974, Portugal experienced repression, hunger, misery, social injustice, labour exploitation, inequality for women, lack of opportunity for non-privileged groups, death and suffering due to the war in the Portuguese colonies in Africa, large-scale emigration, and widespread illiteracy, particularly in rural areas. Many people and groups, particularly those that defended the rights of others, such as the Portuguese Communist Party and the military, suffered years of fighting and repression. During this period, the dictatorial regime, using its police, the Polícia Internacional e de Defesa do Estado (PIDE), was responsible for suppressing any resistance, often using extreme force, imprisonment and murder. Humberto da Silva Delgado was an example of a martyr for the opposition, a man who gave the people hope to believe that Portugal would once again be free from dictatorship. Sadly, he was murdered by the PIDE in Spain on 13 February 1965.

However, under Estado Novo, Portugal benefited from the creation of modern urbanisations, a network of primary schools, and cultural icons like the Galo de Barcelos (the popular rooster symbol). The Marchas Populares were the creation of António Ferro, from the Secretariado da Propaganda Nacional (SPN) and there was a focus on traditional values. There was moregoldin the state banks, and Portugal’s GDP grew from 1950 to 1970 at an average annual rate of 5.7%. But, by the end of the regime, Portugal still had the lowest per capita income and the lowest literacy rate in Western Europe.

After the revolution, Portugal benefited from greater freedom with the acquisition of civil and working rights, the building of a democratic regime, the Movimentos Democráticos, and the creation of workers’ initiatives. However, there were also negatives like the expropriation of private property and decolonisation, with the return of large groups of Portuguese from the ex-African colonies (many having no money or belongings). Certain groups, such as the Forças Populares 25 de Abrill (FP 25), used terrorist measures to enforce their ideals.

In spite of the ups and downs and the period of transition experienced after the uprising, 25 April 1974 is a day of freedom and liberation from an old and fascist regime. In truth, the changes were not achieved overnight; instead, they came about through a complex process that resulted in political, social, and cultural change.

So, how did the Portuguese find out about a military operation that was taking place in Lisbon? It was through the Rádio Clube Português and the newspapers. Many people had an understandable fear and agitation about what would happen and whether the operation would succeed. Therefore, the MFA addressed these concerns through a radio broadcast. They transmitted their manifesto, clarifying how they intended to undertake the operation, outlining their goals, and appealing to the population to remain calm. The manifesto included mention of a party which would manage the country’s affairs in the days following 25 April, i.e. the Junta de Salvação Nacional. This new party would embrace three Ds: Democratize, Decolonize and Develop.1

How did the events of 25 April 1974 affect the local political structures of the Algarve? In the words of Colonel José Glória Alves, “[in the Algarve], the 25th April just happened three days later” (“No Algarve, o 25 de Abril só aconteceu três dias depois”)2. In other words, it took this long for the news of the uprising to reach the Algarve.

Interestingly, the old political systems, those chosen by the previous political regime, were still in charge until the new Decree Law n.º 236/74 was implemented on 3 June. So how did they manage the situation until new political bodies could be established? This is an interesting question, particularly in terms of the official approach taken by each council. The Livros de Atas de Vereação / de Reuniões de Câmara (the book containing the minutes of the meetings) registered the following:

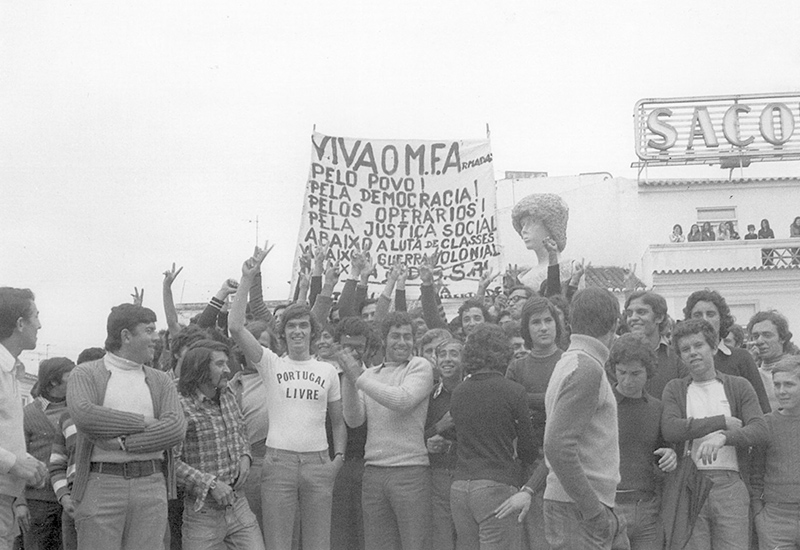

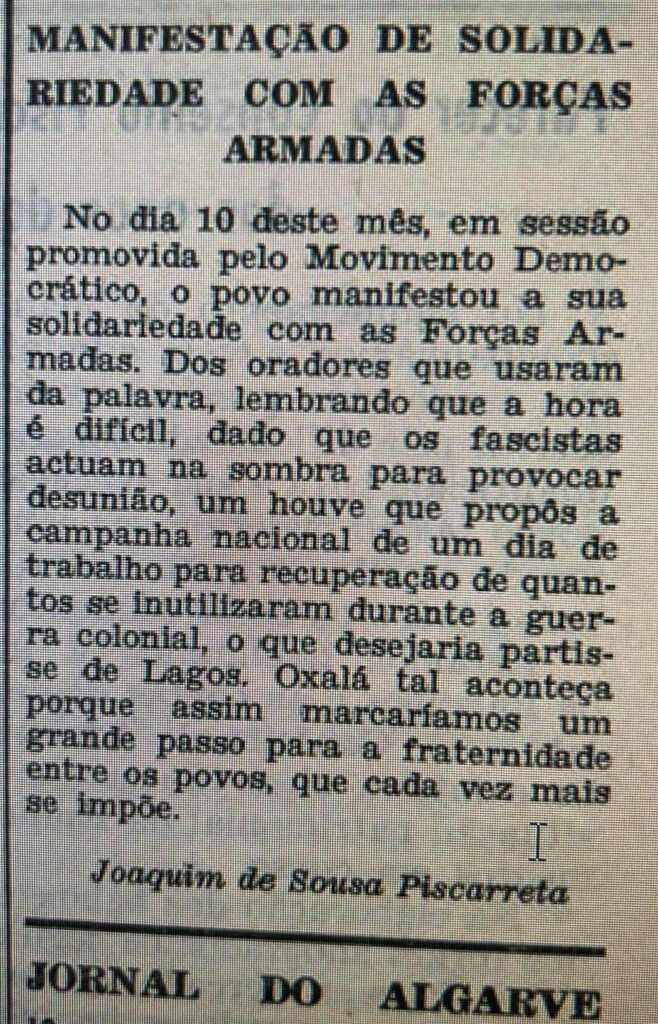

The councils of Lagos, Vila Real de Santo António, Olhão, Tavira and Loulé all held meetings during the month of April where it was discussed what had happened. The meeting in Lagos was convened especially to evaluate the political climate. It was very well attended by the general public and involved some lively discussion. The records show that there was considerable tension between the Executive Board and some of the public in attendance, such as with the architect José Veloso and the artist Deodato Santos. It is also interesting to note that the President of the Câmara expressed support for the military operation and also sought clarification regarding the political position. However, he agreed to maintain the current political status in order to guarantee general order. The President also made a reference to a public demonstration that had taken place on Saturday, 27 April in Gil Eanes Square that he had not been made aware of and into which he says that he was not invited. The demonstration was very well attended by the public.

Lagos, Vila Real de Santo António, Tavira and Loulé councils all decided to send a telegram to congratulate both the military on their successful operation and the Junta de Salvação Nacional. Olhão council was more cautious. Their executive board accepted and agreed with the programme established by the Junta de Salvação Nacional but chose not to communicate their position in order to avoid clashes.

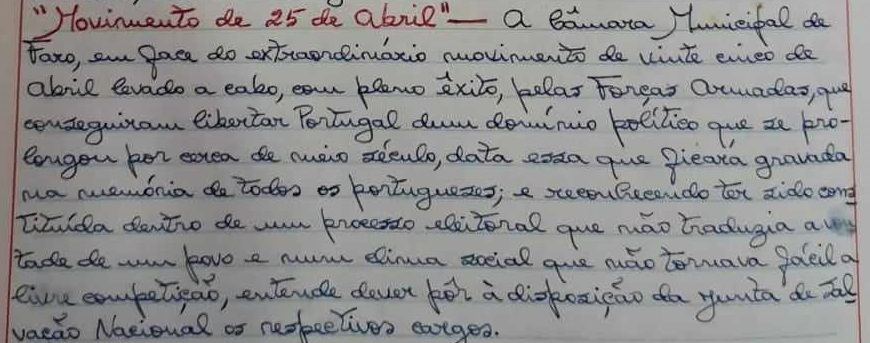

Aljezur, Lagoa and Faro councils all held meetings on 2 May to discuss events and also agreed to send telegrams congratulating the Movimento das Forças Armadas or the Junta de Salvação Nacional. In the meetings of Aljezur and Faro, this was one of the items for discussion along with others regarding general administration. In Lagoa, the meeting was convened especially to evaluate the current political situation, and the meeting minutes reference recent events, but little discussion is noted.

Both Aljezur and Lagoa issued short statements compared to Faro whose statement was longer and warmer: “… the extraordinary movement of 25 April taken by the Forças Armadas freed Portugal from a political regime that lasted almost half a century … and recognise that the câmara was established in an electoral process that did not represent the will of the people … join the Forças Armadas movement unconditionally….”

In its meeting on 2 May, Faro decided to designate street names with significant dates, i.e., 25 April and 1 Maio (to represent the workers). However, these new street designations would not replace the old street names that were linked with the dictatorial regime, as had happened in other councils. The public does not appear to have participated in these three meetings.

In Silves, the subject was discussed at its meeting of 7 May along with other matters relating to general administration. The câmara congratulated the Junta de Salvação Nacional and demonstrated their agreement to cede power to that party, indicating that normal activity would continue until a replacement was in place. It was also agreed a telegram would be sent to the President of the Junta de Salvação Nacional to congratulate him and inform him of the outcome of the meeting. This telegram was also published in two national journals: Diário de Notícias and Diário de Lisboa. The information also noted that a number of people had requested that the câmara change the names of some streets to 25 Abril.

Monchique câmara’s meeting of 2 May makes no mention of the military operation. This is curious because, in Foia, mountain communication equipment from Guarda Nacional Republicana, Guarda Fiscal, PIDE and from the Legião Portuguesa was installed at its highest part. This equipment, crucial to communication with the Algarve, was disconnected by the military from the 25 April movement, namely through the involvement of Colonel José Glória Alves.

Again, in Monchique câmara’s meeting of 20 June, it’s noted that the new party from the provisional regime, the Comissão Administrativa da Câmara Municipal de Monchique, would take power, although no reference is made to the military operations of 25 April.

There is a similar position in S. Brás de Alportel, which also made no mention of the movement. The executive board in charge remained until 28 June, when the Comissão Administrativa took charge. During this period, there are no references to the military operation, and the work of the câmara continued as normal. There was a proposal from the Movimento Democrático to change the avenue named after the dictator, António Oliveira Salazar, but this question was delayed (information provided by the Arquivo Municipal de S. Brás de Alportel).

There is an interesting anomaly in Albufeira. The 1974 meetings record book was destroyed at that time. There were many difficulties in the administration of the câmara until the arrival of Colonel Glória Alves (information provided by the Arquivo Municipal de Albufeira), which might explain this.

In the Algarve, the response from the local power structures to the revolution was progressive. Everything was new and anything could happen. Today, after 50 years, we should say thank you to all those who were stronger than their fears and continued with the actions that secured the freedom and rights the Portuguese enjoy today.

The 25th of April was and is a beautiful, bright day. It is a day of freedom when the rights of everyone are respected. “May freedom be with us all.”

Acknowledgments: Lynn Williams (proofreading) and the following archivists who provided us with copies of the minutes of the meetings: Arquivos Municipais de Lagos (Dora Matias); Vila Real de Santo António (Madalena Guerreiro and Alexandra Cordeiro); Olhão (Helena Vinagre and Pedro Bandarra); Tavira (Isabel Salvado); Loulé (Nelson Vaquinhas); Aljezur (Isabel Canais); Lagoa (Diogo Vivas); Faro (Tiago Barão); S. Brás de Alportel (Vera Gonçalves); Albufeira (Sónia Negrão), and to João Gonçalves from the Câmara Municipal de Silves and Marisa Sampaio from the Câmara Municipal de Monchique.

References:

AM Lagos – Ata da reunião de Câmara de dia 29 de abril de 1974 – Ata n.º 9, fl. 86. Livro de Atas de Reunião de Câmara n.º 32. PT/AMLGS/CMLGS/B/001

AM Vila Real de Santo António – Ata da reunião de Câmara de dia 29 de abril 1974, fl. 45.

AM Olhão – Ata da reunião de dia 29 de abril. Livro de Atas das Sessões de Vereação. PT/MOLH/CMOLH/B/A/001/0058;

AM Tavira – Ata da reunião da Câmara Municipal de Tavira, n.º 9/1974 de 30 de abril. Fundo da Câmara Municipal de Tavira, Livro de Atas n.º 62, fls. 8 e 8 verso. Cota: AMT/CMT/B/A/001;

AM Loulé – Ata da reunião de Câmara de dia 31 de julho de 1974. Ata n.º 16, fl. 57. Atas de Vereação 1974. PT/AMLLE/CMLLE/B-A/001/00180

AM Aljezur – Ata da reunião de Câmara de dia 2 de maio de 1974.

AM Lagoa – Ata da reunião de Câmara de dia 2 de maio de 1974 – Ata n.º 8-A/974.

AM Faro – Ata da reunião de Câmara de dia 2 de maio de 1974, fl. 50

AM Silves – Ata da reunião de Câmara de 7 de maio de 1974, fl. 27.

CM Monchique – Ata da reunião de Câmara de dia 20 de junho 1974 – Ata n.º 11.