The public holiday on April 25 marks the anniversary of the ‘Carnation Revolution’ in 1974, which saw the end of dictatorship and the eventual emergence of Portugal’s modern democracy. Seen by many as romantic, it was, in fact, the result of the country’s third military coup of the twentieth century.

The 1974 revolution marked the end of the ‘New State’ era, which began after a military coup in 1926, ending Portugal’s First Republic. The state which emerged was very much the creation of Antonio Salazar, whose dictatorship began in 1933. The state he controlled was ultra-conservative and corporatist. Economic power was centred on a small number of major businesses headed by families linked to the regime’s high command. The state was also nationalistic, advocating a vision of Portugal based on its heroic past, from the 15 century, as the nation of discoverers. That attitude led the Salazar regime to adopt a hard line towards the country’s colonies.

After the Second World War, other European colonial powers, such as Britain and France, ended their colonial era and steadily dismantled their regimes, granting independence to former colonies around the globe. But Salazar took the opposite approach, believing that dismantling the colonies would dishonour Portugal. It was a fatal error which ultimately brought about the events of April 1974.

Salazar’s state was anti-democratic and, to snuff out opposition to his rule, his state deployed secret police, later known as the Directorate-General of Security (DGS). Although elections were held periodically, opposition candidates were hounded and denounced. The regime managed to complete the democratic mockery by consistently winning 100% of the seats in the country’s supine Parliament.

Salazar suffered a stroke in 1968 and was replaced by a close ally Marcello Caetano, previously the Rector of the University of Lisbon. Caetano was an uncertain dictator. At first, he attempted to smooth off the roughest edges of the regime. He tried to rein in the excesses of the DGS and he granted a degree of press freedom. However the hard-liners in the administration fought his attempts at modest liberation and the measures were eventually dropped. While Caetano was trying to reform the regime’s domestic aspects, the seeds of its destruction were being planted in the colonies.

Rebel movements pressing for independence grew in all of Portugal’s main colonies, particularly in Angola and Mozambique. Inspired by the success of independence movements in other European colonies, the rebels became more determined as the regime in Lisbon became more resistant. Portugal thus found itself fighting numerous battles against rebel movements in several parts of Africa. As rebellion mounted, the regime threw more resources into its attempts to quell the movements. At home, it widened conscription to increase the size of its army, and at the peak of its efforts, military spending to fight the colonial wars was consuming 40% of the state’s budget.

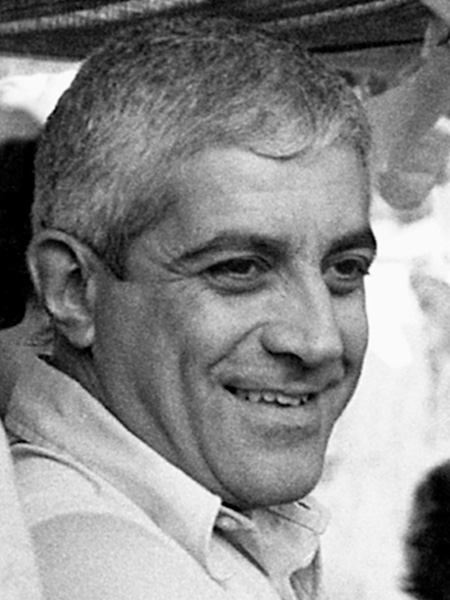

The autocracy’s colonial policy was unpopular with the public generally. But it was even more unpopular within sections of the military – who saw themselves enmeshed in unwinnable conflicts. Tens of thousands of young men were leaving Portugal to avoid the draft. Within the military, opposition to the regime’s colonial policies resulted in the emergence of the Armed Forces Movement (MFA), made up of officers who wanted decolonisation abroad, and free elections and the end of the secret police at home. From the early 1970s, the MFA began plotting the overthrow of the regime. The chief strategist, working from Guinea, was Otelo Saraiva de Carvalho.

By 1974, the plans for the coup were complete. The MFA had many supporters at the professional mid-rank level of the army, inspired by the main aims but also disgruntled by reforms which were seen to give conscripts advantages over professionals.

The signal to begin was the broadcast of Portugal’s Eurovision entry on the radio at midnight. Quickly, tanks took key positions in Lisbon, seizing control of bridges, the airport and government buildings. Caetano fled to the headquarters of the DGS but eventually surrendered to Antonio Spinola, a key figure in the MFA and a former Armed Forces minister, ending up exiled in Brazil. Spinola followed him after his attempt to form a government after the coup failed.

The public celebrated the military coup and the collapse of the dictatorship. Many of those rejoicing in the streets on the morning of 25 April placed carnations in the barrels of the soldiers’ guns, giving the revolution its popular name. The revolution was almost bloodless. Four people died, shot by agents of the DGS.

A once all-powerful regime had been toppled by those on whom it depended on fighting its cause. The immediate aftermath was messy, with attempts at a counter-coup. New democratic movements squabbled. It took two years to reach stability, with the founding of a new republic and free elections in 1976.

Henry Kissinger’s pithy observation was that Portugal avoided falling into the abyss after 1974, thanks to joint work between the MFA and the Portuguese Communist Party.

Happy Freedom Day!

James Plaskitt is a former member of the UK’s parliament, where he served as a minister in Tony Blair’s government. He is now retired in the Algarve.