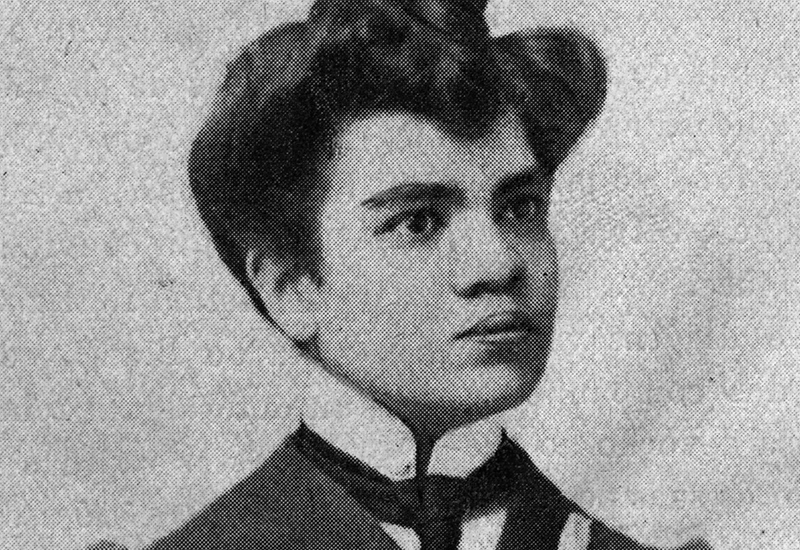

Later this year, the Portuguese-speaking world will commemorate the 50th anniversary of Virgínia Sofia Guerra Quaresma’s death (1882–1973). Now a publicly praised women’s rights activist and writer, she was the first female journalist in Portugal to find a voice in a prejudiced society.

The youngest of the three Quaresma children was born in Elvas in December 1882. She was baptised Virgínia, which means maiden/pure/virgin.

Virgínia’s mother came from an enslaved African family. Her father, Júlio César Ferreira Quaresma, held a commission as a brigadier general in the Portuguese army, so the family had enough money to provide a proper education for all three children.

Like her mother, Virgínia quickly learnt that, in order to survive and be able to go on without a guilty conscience, one must fight and stand strong no matter. So, Virgínia studied at the Faculty of Arts, being one of the first women graduates with a masers degree from the University of Lisbon. Then, she was appointed to a public commission to study women’s education in Europe (France, Italy, Switzerland and Germany.)

A journalistic career followed, resulting in Virginia becoming the first woman to pursue a professional career in journalism in Portugal. Virgínia’s authoritative contributions were much appreciated by feminist journals, such as O Mundo – Jornal da Mulher, Sociedade Futura, Alma Feminina, O Século, and A Capital. Some of her key topics were: pacifism, suffrage, access to divorce, equal pay for work of equal value, access to education, the right to work for married women, and the right to live free from violence and discrimination. After 100 years, it is still considered a miracle how she managed to avoid censorship and persecution for her unswerving analysis and commentaries published under those hypocritical conservative regimes.

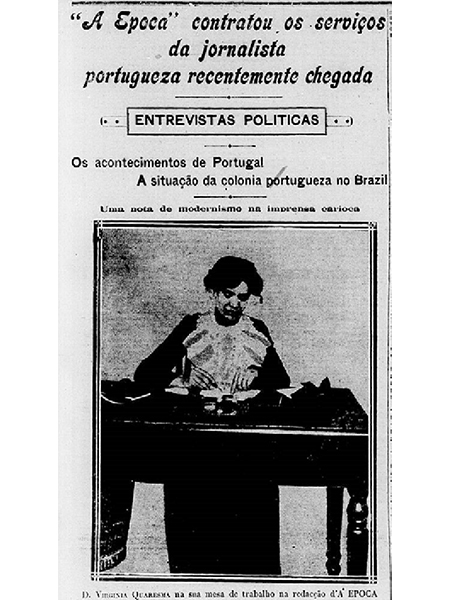

Virgínia Quaresma in the newsroom of A Época in 1912 © Jornal A Época (RJ)

Moreover, she was openly living as a gay woman at a time when both the Church and the laic society were severely homophobic and decreed a ban on ‘subversive behaviour’ in public places. Any sexual orientation which differed from the ‘approved’ one had to be hidden and criminalised. Fearing bad consequences for them, Virgínia moved to Brazil with her life partner Maria da Cunha, where she continued to advocate feminism and write on matters of education and women’s rights until Maria’s sudden death ended five years of travels within Brazil and the Americas. Virgínia Quaresma returned to Portugal in 1917; however, she returned to Brazil in 1933 with Maria Torres, her new partner – who died there as well. After this second tragedy, Virgínia returned to Portugal once more in 1964 and never left the country again.

In October 1973, Virgínia Sofia Guerra Quaresma departed this life at the age of 90. She died with a clear conscience, knowing she had done all she could to help others, and had tried to change society’s mindset.

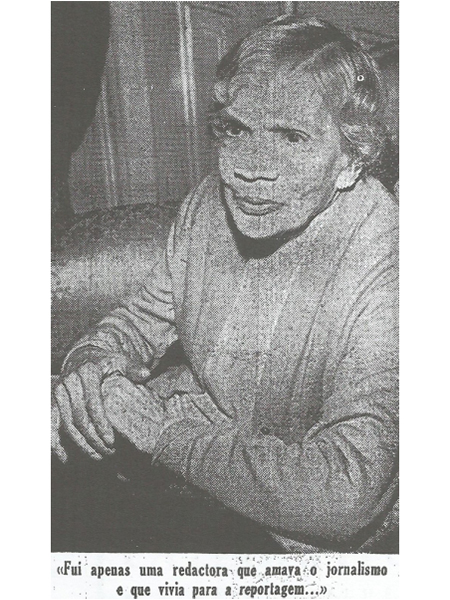

Virgínia Quaresma “I was just an editor who loved journalism and lived for reporting” © Para uma História do Jornalismo em Portugal

Virgínia’s heritage is piously celebrated nowadays as being one of the first mighty promotions of black feminism, both in Portugal and Brazil: the journalist’s name was given to a street in Bairro de Caselas in Belém, and, along with other brave women, her likeness appeared on one of the stamps issued in 2010 to pay homage to their heroism. The public University of Aveiro, founded in 1973, the year of the death of our heroine, grants The International Prize in Cultural Studies ‘Virgínia Quaresma’ in recognition of her achievements. The award is given every two years for “Career” and “Best Doctorate Thesis in Cultural Studies”.

Sometimes we forget too easily how lucky we were to be born and bred in a more or less decent society – at least when it comes to respecting the basic human rights of the people. I invite you all to try a fictional exercise: imagine yourself as you are today living in almost any European society back in 1890–1930. If you were a woman, you were very lucky to be seen as anything more than a voiceless home and kitchen appliance, tightly chained to your biology in a conservative world of sexism and patriarchy. Never forget that, in times gone by, politics and community were designed and run by men seeking their own (male) interests. In addition, imagine living at a time when any sexual orientation other than straight was criminalised, a time when belonging to any ethnic minority was a mark for life if not a serious capital sin.

The circumstances in which we live change constantly; life today is completely different than it was a mere century ago. We can only imagine living under the misogynistic and ultra-conservative regimes of the early 20th century.

Quaresma’s fruitful career as a journalist – her international action for women’s rights, equality in education for boys and girls, support for democracy, the republican cause and pacifism – should be celebrated for its role in establishing the rights we enjoy in Portugal today.

Main image: Virgínia Quaresma © A Universidade de Aveiro