In this new series, we are going to investigate the key figures who have shaped Portugal over its long history. We will meet monarchs, explorers and politicians. But we begin with someone who never existed – Prester John. But the belief that he must exist and the powerful myth that surrounded him shaped Portugal.

To our contemporary minds, this is a very odd tale. But to understand it, we have to take our minds back to a different age – to a time when the surface of the earth and its lands and seas were barely understood, a time when religion, rather than nationhood, ideology or politics, was the principal means of identity. In Europe, this period came just after the end of the 400 years of Islamic domination. After a long struggle, Christianity had been re-established, but it still felt itself under threat from a combination of known infidels, and unknown lands and peoples.

The fragile rule of Christianity in Europe in the 12th century needed to believe there was something out there to secure its place and lead it to an ultimate victory over its Islamic enemies. Militant Christians dreamed that they could work their way to alliances with other powerful Christian forces in the east and, in a pincer movement, overcome the forces of Islam. It was the notion of Prester John that provided the belief and the hope they desired.

It was a dazzling myth. Prester John was believed to be a fabulously wealthy king who dwelt somewhere in the east – possibly India (although the notion of India at this time was so vague that it included much of modern Asia). He was king over many kings. He lived in a crystal palace with walls made of gold. He was surrounded by weird and wonderful animals, and he commanded a massive army, ranging from 100,000 to one million soldiers, all of fearsome strength and all of whom fought naked. Most importantly, he was Christian. If only he could be found, an unbeatable alliance against Islam could be formed, and the future of Christian rulers secured for eternity.

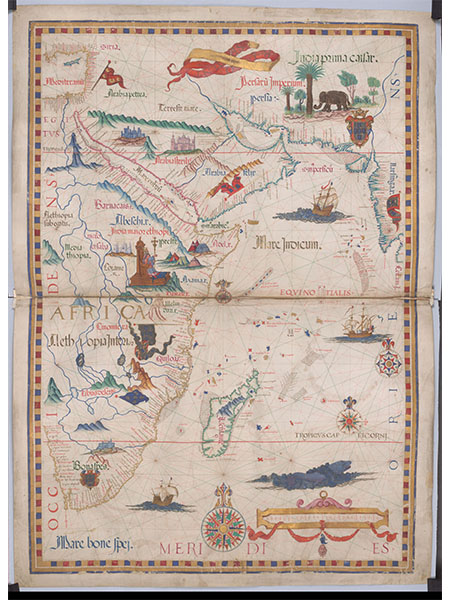

It is unclear how the myth originated. There are sketchy links going back to the myths surrounding the Holy Grail and other accounts claiming that the Prester was actually the father of Genghis Khan. But whatever the origins, by the 12th century, there were delegations to the Pope from rulers seeking help to ward off Saracen attacks and urging the Pope to reach out to Prester John. By this time, there was even a map purporting to show the scale of his vast kingdom. There was also a letter (forged, but by whom we don’t know) from him in wide circulation.

Prester John’s myth persisted and had a powerful hold over the Portuguese. Prince Henry ‘The Navigator’ was heavily influenced by the notion, and his passion for exploration was at least in part driven by the wish to be the one who found and linked up with Prester John. After his failed attempts to find the saviour king, King John II took up the task and, in 1487, sent spies off on a long mission to locate Prester John while also charged with establishing trade routes to India. One of his spies thought he had finally found the elusive Prester when he met up with the king of what is now Ethiopia, only to find out that he was not fabulously wealthy, lacked a naked army, and did not possess the secrets of eternal youth

Undeterred by the many unsuccessful efforts, his successor, King Manuel, committed vast resources to finding the elusive monarch. In commissioning Vasco da Gama to find routes to India, he emphasised the need to locate Prester John. Manuel’s dream was to join forces with the powerful king and press on, with his help, to recapture Jerusalem from Islamic forces

When Vasco da Gama arrived in what is now Mozambique, hopes rose again as he was told about a fabled king who lived far into the interior. But again, he failed to find him. Africans, it turned out, also held to similar myths.

The Age of Discovery is understandably the most famous and most influential part of Portugal’s history. The process was driven by the curiosity of what lay beyond the horizon, the search for wealth, and the desire for conquest and domination of the seas and all the trade that crossed them. But the process was costly and dangerous and the outcome, at least initially, was highly uncertain. The monarchs who funded and inspired the discoverers may not have been as motivated had the process not been interwoven with the powerful desire to establish firm footings for Christianity and expel the forces of Islam. And that vaulting ambition may not have had such a hold had not so many people believed in the existence of Prester John

The long, fruitless search for this mythical King shaped Portugal in medieval times.

Next month: Infante Dom Henrique – ‘Henry the Navigator’