Question: What does a Swedish striker for Sporting and a racing pigeon have in common? Answer: They are both called Gyökeres and are both champions!

Having heard that a Portuguese pigeon named Gyökeres had just given Portugal the world pigeon racing title, Tomorrow decided to delve into the competitive world of pigeon racing, or columbofilia as it is known in Portuguese.

I discovered that the most prominent local club is Clube Columbófilo de Odiáxere, so I set off to find its president and member of the team Santos e Santos, Gonçalo Santos. Thankfully, his wife met me in Odiáxere to guide me to their pigeon loft, which was located off the beaten track in the outskirts of the town.

After meandering along an unmarked road, we reached a farm surrounded by the verdant countryside, which was abundant with long grasses and flowers after the winter rain. I was greeted by Gonçalo, the very glamorous Janna and two large, friendly dogs. I am not sure what I was expecting a pigeon enthusiast to look like, but it certainly was not Gonçalo. He is 30 and works in construction and, in his spare time, his two passions are football and pigeons (pombos in Portuguese). He has a sporty physique and speaks passionately and eloquently.

As we stare into the sky to watch his pigeons returning home, Gonçalo introduces me to his Uncle Nuno and his grandfather, Luís, who make up Santos e Santos. The farm was originally built by Luís but the rest of the family, including Gonçalo, Ukrainian-born Janna and his two children, one of whom whizzes past me on a balance bike, now live there. “We all live in separate houses as neighbours,” explains Gonçalo. My Uncle Nuno also keeps sheep.”

As I sit down to take notes, I am distracted by Avô Luís, who is blowing a whistle. A pigeon lands on the roof of the building opposite and, on hearing the whistle, drops down to perch on a ledge and then enters the building through the pigeon equivalent of a cat flap.

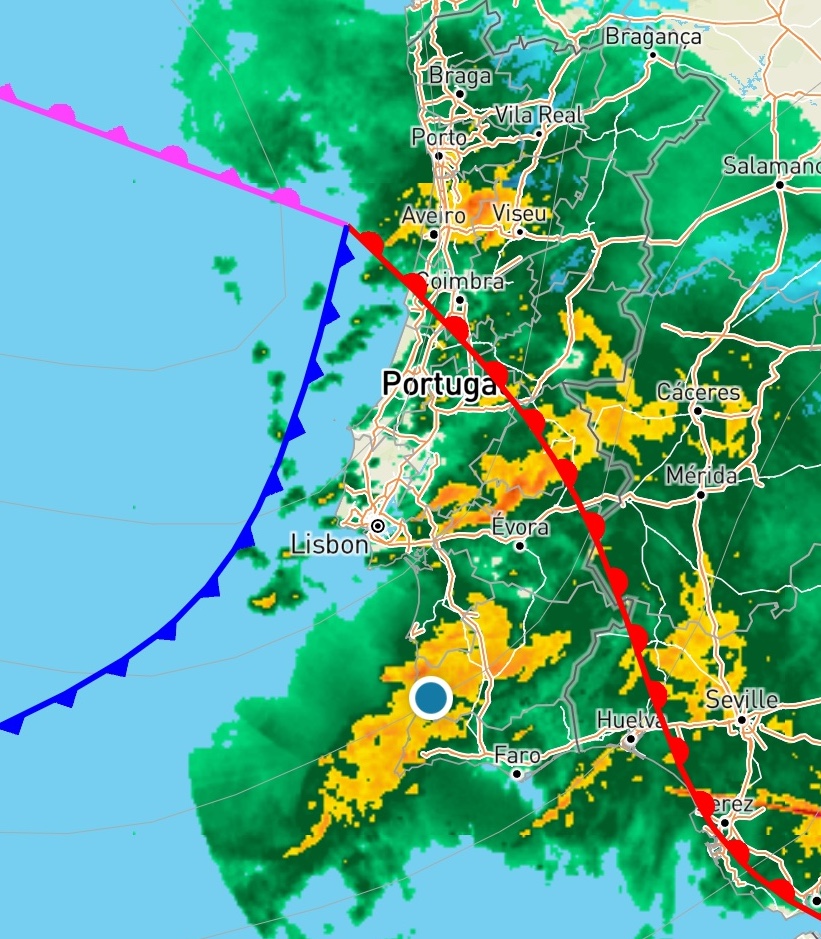

It all seemed very strange until Gonçalo explained to me that they were waiting for the arrival of the last pigeons that were released at 7 am that morning in Nisa in the Portalegre district of central Portugal. It is 413 km away and Google Maps tells me it would take four hours and eight minutes to drive the distance. However, Gonçalo’s fastest pigeon arrived back home at 10:00:48, earning the position of 4th out of 650 fellow pigeon racers. “The whistle is a reminder to the bird to enter the building quickly as they associate it with food,” Gonçalo tells me. “This is important because the ’pigeon flap’ is linked to a machine that records the time they enter their loft via a tag on the pigeon’s leg and is recorded onto a device that officially logs it for the competition.”

The previous day, Saturday, Gonçalo explains, is called ‘basketing day’. His team took 75 pigeons to the club in Odiáxere. Only 25 were there to compete and the other 55 were on a training exercise to learn the drill from the more experienced pigeons. All of the pigeons were then transported to the pigeon club of the Algarve, where a huge truck collected them and drove them to Nisa.

At 7 am, all the competing teams’ pigeons were released. Gonçalo shows me the video. It’s a spectacular sight as hundreds of pigeons explode from the truck in a huge swarm, temporarily blanketing the sky until they all break off, eager to get back home. Gonçalo tells me they often separate the breeding couples, who mate for life, so they have a further incentive to return to their family quickly.

When they get back home, their return is logged and their average speed over the distance is calculated to judge the winner. I wonder if this amazing feat relies on a natural homing instinct or if some training is involved. Gonçalo informs me that it is like a football team and they require some training. At around two months old, they take them to about 5 km from home. They then increase to 150 km and he says that once they have done this twice, they can generally find their way back from any distance.

Luís has been racing pigeons for 42 years, and it was from him and his Uncle Nuno that Gonçalo learnt about the sport and acquired his aptitude for rearing pigeons. They are a family rooted in Odiáxere.

All were born in the town, as well as Gonçalo’s mother and father who are president and vice president of the Clube Desportivo de Odiáxere. There are an astonishing 12 pigeon racing teams in Odiáxere, so it is obviously a local passion.

They take me on a tour of the pigeon loft to see the 115 adult birds and 120 adolescents. I enter with some trepidation as I am not a huge fan of pigeons, but we are not talking about the mangey specimens we see pecking around the streets. These are really beautiful creatures and as I enter their loft, a beautiful soft cooing noise fills the air. Couples sit in nesting homes recovering from their long journey, their heads bobbing as they stare at their visitors. Their home is ventilated to make it pleasantly cool.

Gonçalo tells me that today he will put special drops in their water to protect them from any infections they may have got from the other birds. He also gives them muscle recovery products and protein.

After visiting the ‘nursery’ where female birds are sitting on their eggs and where the chicks will hatch, Gonçalo shows me his medicine cabinet. I am astonished. There are more medications, supplements, lotions and potions than in the average pharmacy! And this, according to Gonçalo, is the secret to success. Just as you would focus on the health of a human athlete, the same can be said for pigeons. As well as three bins containing the best mixes of pigeon food to promote health and stamina, Gonçalo also experiments with vitamins and supplements (some of which are intended for human consumption) to attain the fastest bird.

Gonçalo spends a lot of time on YouTube and the internet researching new techniques. It obviously takes a great deal of time, research, dedication and money and I question why a young guy like Gonçalo is so addicted to the sport? “When the pigeon arrives, it is such a great feeling,” he explains. “I care about the birds and I try to make them healthy so that I will breed a winner.”

Janna rolls her eyes slightly as I am sure she imagines the cost of all the medication in his cabinet would buy her a new wardrobe of clothes! However, she is incredibly proud and supportive. She tells me, “Gonçalo has been the president of the Odiáxere club for three years and he is only 30. He is very dedicated and passionate.” There is also no financial reward on offer, just the honour and trophies!

We pass the pigeon hospital, where some wounded pigeons are recuperating. Then, there is the pigeon bathing area! There is a sink where the birds are washed to remove parasites and clean their feathers once a week.

I am beginning to understand that this is a very competitive sport where the birds are nurtured like premier footballers. Gonçalo tells me that on 31 May, 50,000 pigeons will be released in a competition. And just as in human competition, there are different distances. The short-distance speed is 300 km, the middle distance is 500 km, the long-distance is 750 km, and a race from Barcelona to Portugal covers 1000 km.

Gonçalos, two-year-old, whizzes past us again on his balance bike, and I wonder if he will take on the family tradition in the future. It’s been a fascinating morning, not only discovering the ins and outs of pigeon racing but also meeting a local family who are keeping such a fabulous tradition alive.

As I drive away from this rural idyll, I reflect that this is more than a story about a niche sport. It’s a story about how beneficial it is for knowledge and decades of experience to be passed to the younger generation, made possible by close familial ties. It is a reflection that for us, as well as pigeons, there is no place like home!

Racing pigeons rely on a combination of visual, olfactory and magnetic cues to navigate back home. They use familiar landmarks like roads, rivers and buildings along their routes. Additionally, they possess a magnetic sense that helps them navigate using Earth’s magnetic field. Some research also suggests they may use low-frequency infrasound and even the scents of their home environment to find their way.

Facebook: C Columbófilo Odiáxere Cco