When renowned Brazilian photographer Leticia Valverdes received a Fuji Portugal Residency in 2017, she had no idea how much the artistic grant would change her life.

As a child growing up in the vibrant, cosmopolitan city of São Paulo, Leticia Valverdes spent countless hours with her beloved Portuguese grandmother, Ana. On Saturdays, they shopped together at the local street market. Young Leticia was transfixed by the blood red tomatoes, the sunken eyes of cod fish on ice and the sweet, alluring smell of papaya and pineapple. She remembers her grandmother, touching different fabrics to her skin, explaining the differences in quality and texture between lace, satin and silk.

“She wanted to be a pianist and an actress but the only thing her father would allow her to do was be a seamstress,” explains Leticia. She was also permitted to be a hair model as this didn’t show her face, but most of Ana’s dreams and desires were forbidden. She spent a lifetime telling Leticia, who was the apple of her eye and her first born grandchild, not to allow a patriarchal society to stand in her way.

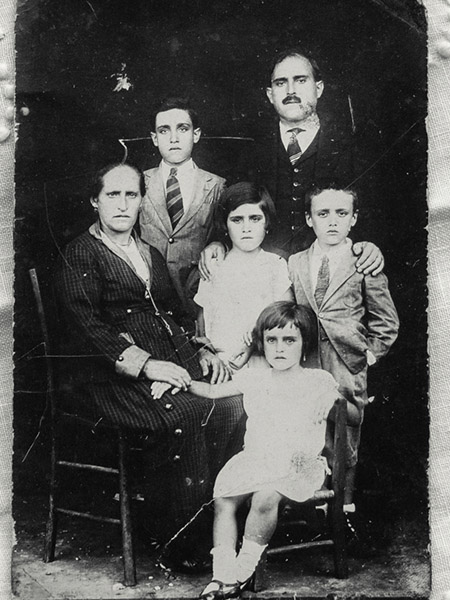

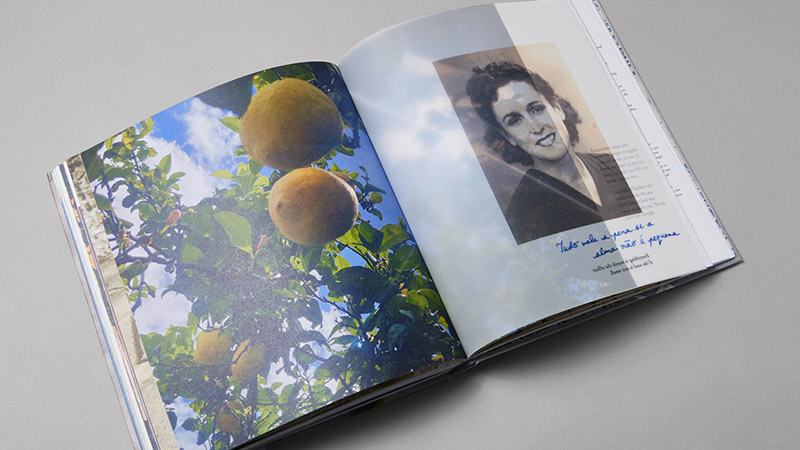

“My grandmother wanted a better life for me,” says Leticia. “She wanted me to have choices she never had, she wanted me to marry a man I loved, and most of all she wanted me to follow my dreams.” One of the many dreams Ana never got to fulfil in her lifetime was returning to her beloved Portugal. By the time Leticia’s family could afford to send her, she suffered from poor health and dementia. Near the end of her life, she talked incessantly about Portugal, about her lost friends there, about the pungent smell of lemons and oranges, about the land she owned there, about her saudade – longing for her homeland – and about the tears on her own grandmother’s face as she watched her children and grandchildren depart in 1921.

Although she was only one and a half years old when she emigrated to Brazil, Ana spent a lifetime dreaming of her return. With bittersweet serendipity, Leticia found a way to fulfil her dream posthumously. Already an accomplished photographer interested in the therapeutic and theatrical aspects of performance photography, Leticia received the Fujifilm Residency in 2017. Eleven years after her grandmother’s death, this grant allowed her to visit the tiny village of Mundão in northern Portugal. She wanted to photograph the place and the people her grandmother had left behind. In 2020, she was awarded the prestigious Via Arts Prize for her work.

“We are the guardians of the forgotten and excluded memories which we inherit in our wombs,” Ana writes in a fictional letter to her granddaughter Leticia in the photo poetry book, Dear Ana. “Do you know, Leti, that you were once a seed in my womb? We have always been connected.”

Sr Antonio Sebastião. At 98 the eldest man in Mundão, when this photo was taken. He was born in 1919 the year before Ana. He has since died.

This powerful physical connection led Leticia to her grandmother’s birthplace on a quest to fulfil old dreams, heal transgenerational wounds and discover lost roots. When Leticia first arrived from London with her fancy cameras and bags of equipment, the villagers in the small parish of Mundão were suspicious. Once she showed them her grandmother’s birth certificate from Mundão and explained why she was there, they began to tell their own stories.

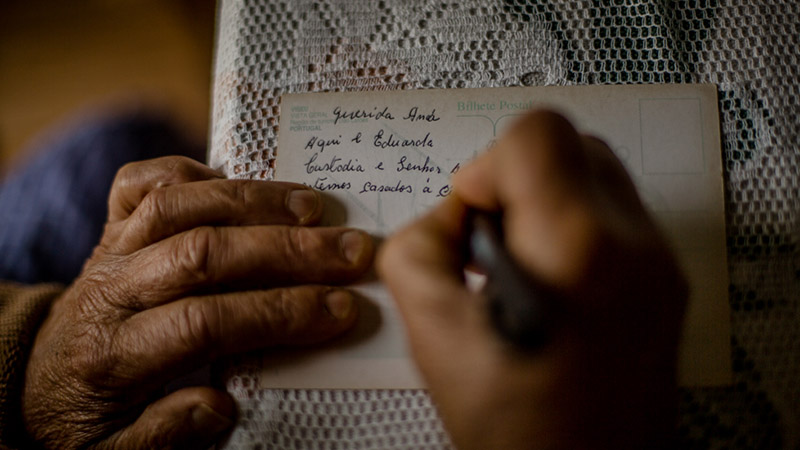

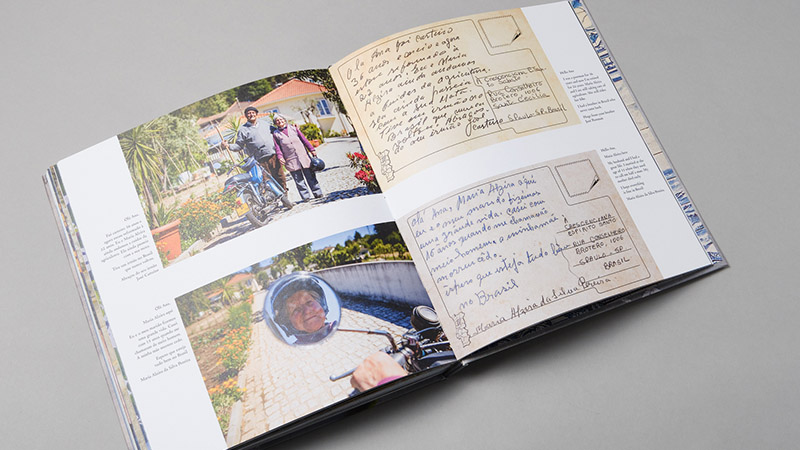

“I shared my saudade and then I asked them to share their own,” says Leticia, who invited the villagers to be Ana’s fictitious friends and write postcards to her deceased grandmother, who they had never met. It was a project designed to instigate participation. “For me, photography has always been about inviting people to be photographed in a way they want to be seen,” says Leticia. “I have a passion for the internal landscape of people as fellow humans. I believe photography can help find our common denominators.”

Eufemia after performing traditional dance in Viseu.

Indeed, these postcards connect Ana to the life she might have led. They fostered healing for Leticia, balm for the transgenerational wound of immigration. They offered Leticia a chance to connect her past with her present. “When I brought her birth certificate to the priest at the small local church, he opened the church books and found her christening certificate. In it, we read that Ana’s godfather had also been her uncle and he was still alive. It was a huge shock to me as I never knew I still had family living there, and it connected me to cousins I never knew I had. It was a moving moment. Many of the villagers were there with me too.”

Leticia also shared details about her grandmother’s life in Brazil, her family’s immigration borne from desperation and starvation in Portugal, her work as a seamstress and her loss of a son who died of cancer at the young age of 21. In their postcards, the villagers speak of their own losses, of their memories of Portugal, of playing in the orchards as children and attending church. “They knew you were gone, but they understood that a person never really disappears if we carry them in our heart,” writes Leticia in a letter to her grandmother.

Interspersed with small pearls of poetry, intimate letters between generations and beyond the grave, the stunning photographs immerse the reader in a journey that is at once deeply personal and profoundly universal. So many of us have left behind beloved family and friends to make new lives in different countries. So many of us long for those we love and cannot be with – especially in these trying times when travel has the added challenge of a never-ending global pandemic.

This, insists Leticia, constitutes the foundation of her work. To find the human elements within photography that connect us all as people, the underlying and delicate filigree of our shared experiences. To focus on our differences is easy. But to find the common ground is often much harder – even when we know there is far more sameness than separation. We divide ourselves over politics, over religion, over race, over age, over gender, and over opinions. But at the end of the day, we are all human. We all have blood running through our veins and hearts pumping in our chests. Leticia endeavours to capture this common ground through artistic photographs that capture shared experiences.

Beyond the healing power of human connection, Dear Ana also tells the story of a young child who emigrated and never made it into any history books. “My grandmother represents one of many,” says Leticia. “She is a symbol of unfulfilled dreams and the love that lives on and is also passed on in the very genes of the people who come after and carry it inside.”

In yet another turn of magic realism, the participatory aspect of Dear Ana continued after Leticia and her family decided to move to Portugal. “I used the sunshine of Portugal to do a chemical process I put on paper then print with sun called Cyanotype,” says Leticia, who moved to Aljezur from the UK in 2020. “I continued to get the sun that she never felt and all the flowers are from Portugal so I intertwined those with her lace to create a devotive aspect.”

In the spring of 2022, exactly 101 years after her grandmother left Portugal, Leticia’s exhibition near Trafalgar Square in London for the Via Arts Prize will open. “I am honoured to be living the life she wanted for me,” says Leticia. This accomplishment adds to the powerful catharsis in her work – for herself, for her grandmother, for anyone who has ever felt saudade and especially for all the unnamed women who have immigrated around the world.

All photos © Leticia Valverdes

To buy the book, you can contact Leticia directly at: www.leticiavalverdes.com/contact-us

For those of you who are local, we will be hosting a book sale near Lagos on 22 January from 2 pm–5 pm so come and get yourself a signed copy and take advantage of no shipping fees. If you’d like to attend, please contact me at meredithmprice@gmail.com