Fruit drying can be traced back to the fourth millennium BC in Mesopotamia, modern-day Iraq, as a way to preserve fruits in the blistering Arabian sun and to enhance the natural sugars of the fruit to be used in various recipes.

This age-old way of preserving fruit would eventually land in Europe after the Arabian takeover of the Iberian Peninsula, where the Arabs cultivated the vast array of fruit trees to which we have become accustomed today. With Southern Europe sharing a similar climate to that of North Africa just a stone’s throw across the Atlantic and Mediterranean seas, it is no surprise that the fruits that once graced the Arab world would soon flourish and become an equally important part of Southern European cuisine.

When the Arabs departed the Algarve in the 14th century following the Reconquista, the fruit trees and the process of drying the fruit were preserved. Following the great earthquake of 1755, which saw the destruction of much of Portugal, the Algarve, through its seaport city of Portimão, began to slowly transform itself into a successful shipping hub for agricultural products which would later be eagerly sought after overseas during the dried fruit boom in the mid 19th century.

The Algarve was and still is famed for its carobs, figs and almonds. Growing in abundance, they made up not only the staple of many local dishes and delicacies but also brought employment to the struggling local economy.

In Portimão alone, there were several smokehouses or fumeiros, each dedicated to drying the many varieties of locally grown fruits and nuts. Although seasonal from August to December, the generally all-female workforce would dry fruit as well as work in the canning factories, which were equally as lucrative at the time. The main hub was the canning factory’Fábrica S. José, which was founded in 1892 and today makes up part of the Museum of Portimão.

The fruits would be sorted, dried and packed in baskets crafted from palm known as empreita, thus forming another workforce of local women who would weave the packing baskets on their doorsteps as a way to subsidise their salaries. This gave a range of employment for locals and made Portimão an industrial hub once again. This was aided by the seventh President of the First Portuguese Republic, Manuel Teixeira Gomes (1860–1941), who was in office from 1923 to 1925 and was born in Portimão and promoted the dried fruit industry.

As well as carobs and figs, there was also a large trade in almonds from the Algarve. There is a famous legend which tells the story of how the Algarve acquired so many almond trees, which was attributed to an unlikely princess. According to the story, an Arabian King named Ibn-Almundium of Chelb (Silves) married a beautiful North European Princess by the name of Gilda, who had been imprisoned during the wars. The royal couple lived happily until the princess began to fall sick. Failing to find a cure, it was suggested that Princess Gilda was suffering from nostalgia for the snow she had always seen in winter back in her homeland, something very uncommon in the dry arid winters in the Algarve. King Ibn-Almundim had a plan and planted almond trees throughout the kingdom to cover the land with white petals and simulate the tone of the snow.

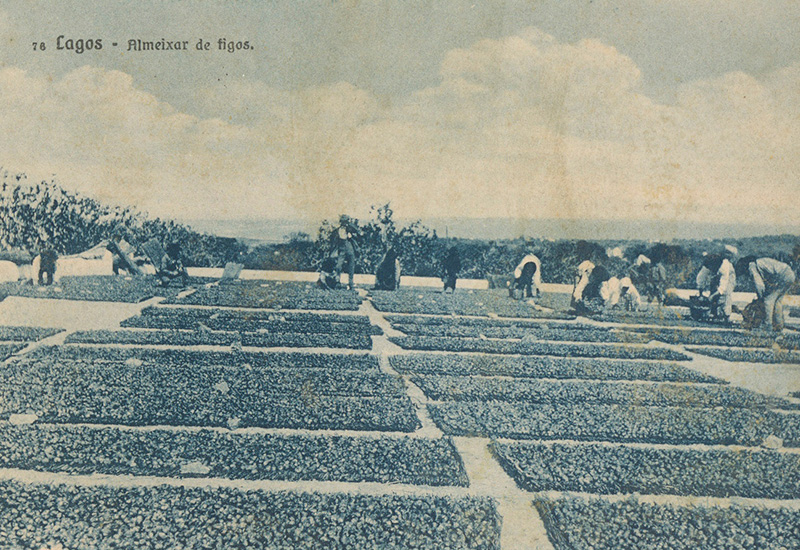

Across the Algarve, farmers would harvest their crops to feed the dried fruit market, which had expanded and was exported around the world. Even high up in Monchique, fruit was dried, demonstrated in the fact that they created their own word, almêxár (translated as the process of sun-drying corn). The general misconception is that the word means to dry figs, but in Monchique, corn was much widely favoured due to the perfect growing conditions high up in the hills.

Taking advantage of the Arade river, which runs through Portimão out into the open seas of the Atlantic Ocean, the Algarve’s homegrown produce and regionally caught sardines were hitting the shelves of stores anywhere from London to New York, all passing through this once small fishing hamlet of Vila Nova de Portimão.

Like many industries, the aftermath of World War II saw the decline in interest for the once flourishing Algarvian dried fruits and canned sardines and, over time, the factories went out of business. Although a handful of hardy farmers still sun dry fruits on a small scale, it’s not as it was.

Today, figs and almonds are imported for use in some of the local delicacies, such as the famous Dom Rodrigo dessert, which is found in many of today’s pastelarias. If you look hard, you can also still find Algarvian-produced almond liqueur and maybe even the odd Algarvian dried fig in your local farmers market, but sadly just not on the scale that once brought Portimão into prominence.

Main image: Figs drying at the almeixar, António Crisógono dos Santos Courtesy of www.fototeca.cm-lagos.pt