As far as oxymorons go, Dancing Stones ranks among the most unusual.

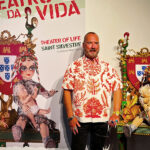

At the top of a narrow country lane just outside of Lagos lies the outdoor workshop of renowned German sculptor Christian Tobin. Just beyond a linear row of statuesque Leylandii trees, a metal gate opens into the space where colossal stones come to life.

Inside, enormous granite stones form an uneven perimeter. A massive piece of spotted granite hangs from the top of a forklift in the centre. Below it, a square granite slab sits atop a circular metal frame. Eventually, after many hours of careful circular grinding – top against bottom – these two pieces of stone will fit together within 1/300 of a millimetre. Precision is paramount to the final sculpture – a piece of kinetic art that will actualize two-ton stones dancing on water.

“This is an extremely rare stone,” Tobin explains, pointing out the dark grey spots that give the silver piece of granite a unique depth. “Normally the darker elements are heavier and they sink to the bottom, so you never see them in the middle of the stone the way they are here. How can that happen?”

Chosen from a quarry in Evora, Portugal, not far from the Spanish border, these specific pieces of rock visually depict a rare and singular phenomena on earth. “I have never seen anything like this,” Tobin adds reverently. For an artist who has spent the last 40 years working solely with stone, this was an incredibly lucky find. They were the perfect choice for his latest commission – a public square in the town of Chemnitz, Germany.

Designed to dance in various directions, the finished sculpture will have three colossal stones of similar sizes placed in a non-linear order. To the naked eye, they will appear to move atop the ground itself, as the bottom half will be set into the square.

“I wanted dancing stones to go along with the dancing houses they are building there,” Tobin explains. Indeed, the nearby architecture is a series of asymmetrical buildings with misaligned windows and uneven angles. As with each and every sculpture, the first part of the work entails travelling to the location, examining the space at different times of the day, understanding what the space will be used for, and asking lots of questions.

“I never know where the idea will come from,” says Tobin, who is credited with founding the entire field of kinetic stone sculptures and has worked all over the world, including in Japan, the United States, Switzerland, Finland, Germany and South Africa (to name but a few).

Like many of the greatest inventions, Tobin discovered the technique by accident. As a student at the Munich Academy of Fine Art in the early 80s, he separated two large stones to create a sculpture in which one stone would float on top of the other. His failed attempts led to an incredible realisation. The ball bearing between them started to roll on top of the water by itself. This gave Tobin the idea to try the same thing on a much, much larger scale.

In 1983, he created his first spherical fountain for the International Horticultural Exhibition. A small amount of pressure from the water creates the movement of stone that weighs up to several tons, which means that even children can move them easily and safely. Since that first spinning globe, Tobin’s creations have expanded to include gigantic sundials and stone works. Although they all share a kinetic ability and uncanny physics, each one presents a new challenge.

In his current piece, the three stones will have different radii of movement to create visible differences in the way they dance. Once the creation and testing phases are completed, Tobin will return to Germany and work closely with the technicians responsible for the light, sound and water elements to perfect the sculpture.

Tobin jokes that he is well-respected now because he has gray hair. Despite being one of the most famous contemporary sculptors in the world, he maintains a charming humility and childish wonder regarding his accomplishments. “I treat everyone the same when it comes to my work,” he says. “From the big boss to the one who shovels the dirt for the foundation.”

When I ask what philosophy inspires his work, he points to the text on his coffee mug: less is more. Tobin hopes to create more kinetic sundials that forge art, physics and astronomy in the future. For now, it’s one project at a time. “After all,” he jokes, “it’s not easy to make three-ton stones dance”.

Photos and video © Reuven Levitt