In 2016, a cave was discovered during the construction of Portimão’s new water treatment plant at the Companheiro site. Investigations of the cavity revealed archaeological remains from the Middle Palaeolithic occupations (a stage in human prehistory, lasting from approximately 300,000 to 40,000 years ago). This exciting new discovery led to further excavations and new findings under the Finisterra project, which explores the last of the Neanderthals in Portugal.

When Tomorrow asked me to find out more, I found myself joining a group of about 20 interested participants, ranging from academics to members of the public.

The Finisterra project aims to identify the population trajectories and cultural dynamics of the last Neanderthals in the far west of Europe. It is funded by the European Research Council, with logistical support from the Portimão City Council and is currently underway at the Companheiro site. After its discovery, the Companheiro Cave was investigated by Dr João Cascalheira and Professor Nuno Bicho of the University of Algarve (UAlg). The open day event I attended was spearheaded by Vera Freitas from Portimão museum and the detailed presentation was given by Professor Dr Cascalheira. The event was the fourth in a series of events which have garnered overwhelming interest.

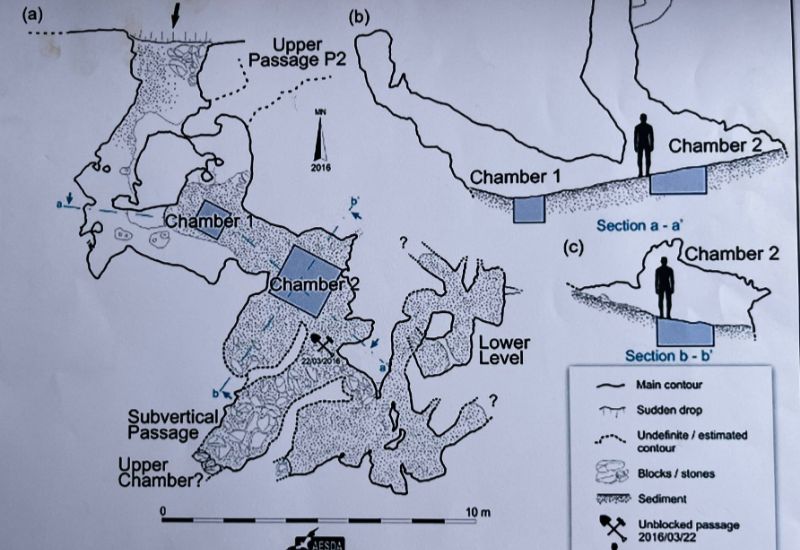

The presentation began with an explanation of how things proceeded after the initial discovery. After realising that the cave was indeed a prehistoric dwelling, archaeologists from the University of Algarve were brought in to carry out careful digging and meticulous analysis of artefacts and methods to facilitate further excavation without damaging the site. Geophysics technology was used to identify underground cavities and an excavator was used to carefully uncover an entrance to the cave. The work is continuing, and maps have been drawn to show the results to date.

Next, we attendees learned how the caves came to exist. The geology and creation of the Algarve caves involved the process by which soluble rocks like limestone are dissolved by groundwater, creating cavities. This also explains why Algarve water is considered hard water: it’s due to the calcium content from soluble rock.

The Iberian Neanderthals

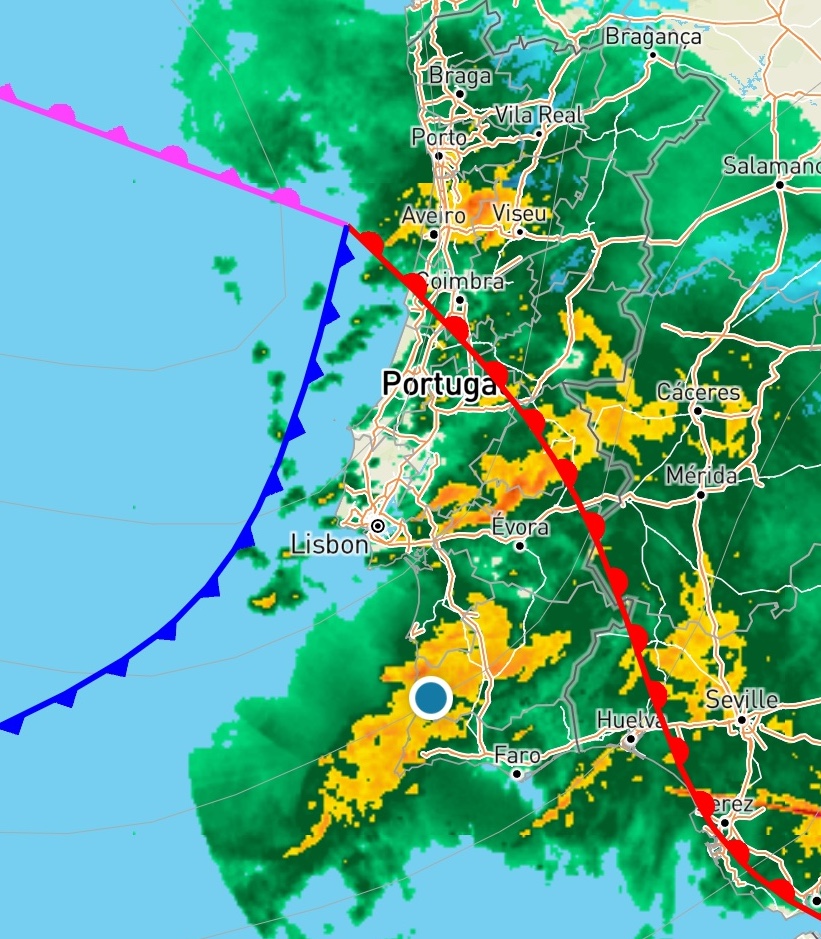

In the Iberian Peninsula, there are many known sites of Neanderthal occupation and there are a lot more to be discovered. The green map shows the locations of some of the most important sites of late Neanderthals and early Homo sapiens before the discovery of the Companheiro site.

Bone remains found and identified in the cave include rhinoceros, deer, horse, turtle and aurochs (an extinct bovine species). No Neanderthal bones have yet been identified, but some possibilities are still being analysed. Some bones were previously classified as belonging to a primate, so the attribution of these samples as Neanderthal remains is only speculation at the moment.

Stone tools have been observed – some for scraping, others for chiselling or even cracking open bones to get at the nutritious marrow. Dr Cascalheira explained that some of the stone tools were not from this area, speculating that perhaps they were traded with other groups from different regions or that travelling widely was part of the Neanderthal lifestyle. In other Neanderthal sites, arrow and spear tips have been found, confirming the description of Neanderthals as hunter-gatherers. Also, carvings and cave art have been identified in some sites in Spain, so anticipation for exciting finds at this Algarve site is high.

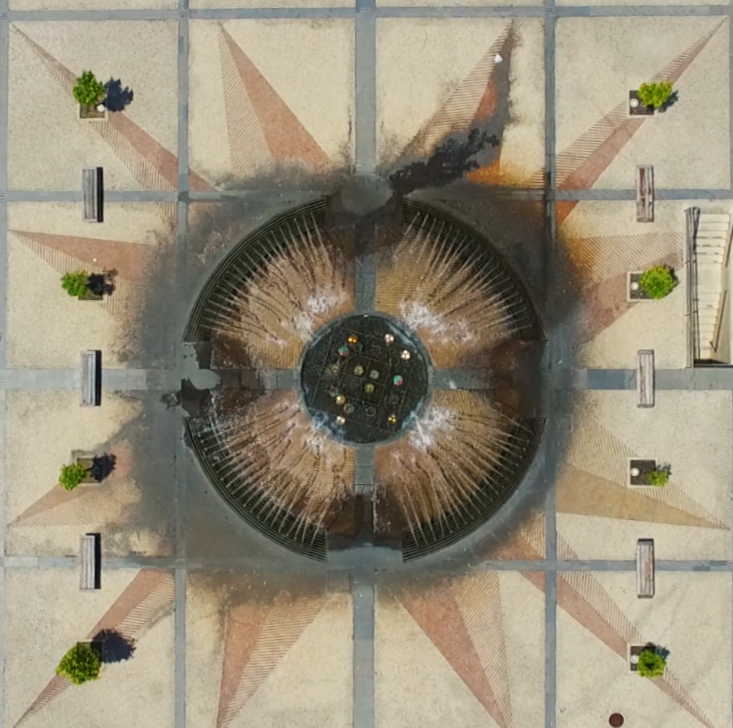

After the presentation, we climbed down to the opening of the cave. It was surprising to see its small size. Although it is currently not possible to visit the cave’s interior, it consists of two small horizontal chambers and several corridors, with an estimated length of approximately 10 metres (see map).

The Human Genome Project

In 2003, the Human Genome Project was completed. By 2009, advances in DNA extraction made it possible to recover genetic material from Neanderthal fossils. In 2010, the Neanderthal genome was compared to that of modern humans from different continents. The key result was that people of non-African ancestry have up to 2% Neanderthal DNA, showing that interbreeding occurred roughly 50,000 years ago.

Millions of years ago, humanity was not a single species. The Earth was home to six distinct human species, each adapted to its environment, with its own tools, culture and intelligence.

Homo habilis (2.4–1.4 million years ago)

Known as the “handyman”, they were among the first to use stone tools. Living in Africa, Homo habilis marked the beginning of human technological development.

Homo erectus (1.9 million–110,000 years ago)

They were great travellers – the first humans to leave Africa. Homo erectus mastered fire, built shelters, and lived in organised groups.

Neanderthals (Homo neanderthalensis) (400,000–40,000 years ago)

Strong and intelligent, they adapted to Europe’s cold climate, crafted tools, and even buried their dead – showing early signs of emotion and culture.

Homo floresiensis (100,000–50,000 years ago)

Often called the “Hobbit humans” due to their small stature, they lived on the Indonesian island of Flores, surviving in isolation for thousands of years.

Denisovans (200,000–30,000 years ago)

Mysterious, and recently discovered through DNA evidence, Denisovans lived in Asia and interbred with both Neanderthals and modern humans.

Homo sapiens (300,000 years ago – present)

The only surviving species – us.

With advanced language, creativity and adaptability, Homo sapiens spread across the world, shaping civilisations and the modern world.

Though the others vanished, they live on in us – through shared DNA and the evolutionary steps that made us who we are.

Co-ordinator: Archaeologist, Vera Freitas, Portimão City Council

+351 282 470 837 / +351 965 525 031