For many families, Christmas simply wouldn’t feel complete without a Nativity scene at its heart. This timeless tableau has graced homes, churches and town squares for centuries. In Portugal, the tradition has taken on a life of its own, evolving from a simple devotional display into intricate works of folk art.

The Nativity can trace its roots back to the 13th century, when St Francis of Assisi created the first live Nativity in Greccio, Italy, in 1223. Inspired by his pilgrimage to Bethlehem, St Francis wanted to make the Gospel story tangible for ordinary people, especially those who couldn’t read.

Over time, Francis’ tableau of live actors and animals evolved into static displays featuring carved wooden figures depicting Christ’s birth. With much of the medieval population illiterate, the spread of Nativity scenes across Christian Europe became an ideal way to preach the Gospel to the masses.

While early displays featured the Holy Family, shepherds, and sometimes an angel, the Three Kings arrived later to represent the Gospel of Matthew (2:1–12), which describes “wise men from the East”. Although many parts of Europe favour a traditional Nativity scene complete with a wooden stable, across the Iberian Peninsula, Portugal and Spain take things further – often creating entire miniature villages to resemble the town of Bethlehem and afar.

For those of us who remember being roped into the school Nativity play, we can thank St Francis for that particular pleasure. Personally, I much prefer the figurine displays which evolved from this ancient tradition, especially the delicately crafted villages that almost look lifelike, which have grown in popularity across the Latin world.

From Praesaepium to Presépio

The Nativity, known in Portuguese as Presépio, derives from the Latin praesaepium, meaning an enclosure for animals. Unlike modern versions of the Nativity featuring a wooden stable, the word praesaepium likely refers to a more realistic setting – an enclosed area beneath a dwelling, almost like an open cellar used to house cattle and warm the home above. Over time, the word evolved into presépio, retaining its original sense of a manger but expanding to mean the entire Nativity scene.

In the early Christian world, the term was used as far back as the 7th century, notably in Sancta Maria ad Praesepe (Saint Mary at the Manger), a chapel within the Basilica of Santa Maria Maggiore in Rome, where a relic of the manger is believed to be housed.

Over the border in Spain, the Nativity is known as Belén, which literally means Bethlehem, the birthplace of Jesus. The English word Nativity however, comes from the Old French nativité, which entered the English language via Latin nativus (born) and nativitas (birth). The first recorded use in English dates to the 12th century as nativite, referring specifically to the feast celebrating Christ’s birth, now called Christmas.

Portugal’s Passion for the Presépio

The Nativity appeared in Portugal around the same time it spread across Europe, some 800 years ago. But the Portuguese have embraced the tradition with such enthusiasm that they now boast some of the largest and most elaborate Nativity scenes in the world. These often feature miniature villages complete with running rivers, smoking bonfires and flickering candlelight. The Iberian Nativity has become an art form in its own right – going beyond the birth of Christ to depict the wider town of Bethlehem as it might have looked over 2,000 years ago.

In 2013, the town of Santa Maria da Feira, 30 km south of Porto, earned a place in the Guinness World Records for the most mechanical figures in a Nativity scene, 162 to be exact. The remarkable display was constructed by Manuel Jacinto and has become one of the most beloved in the country.

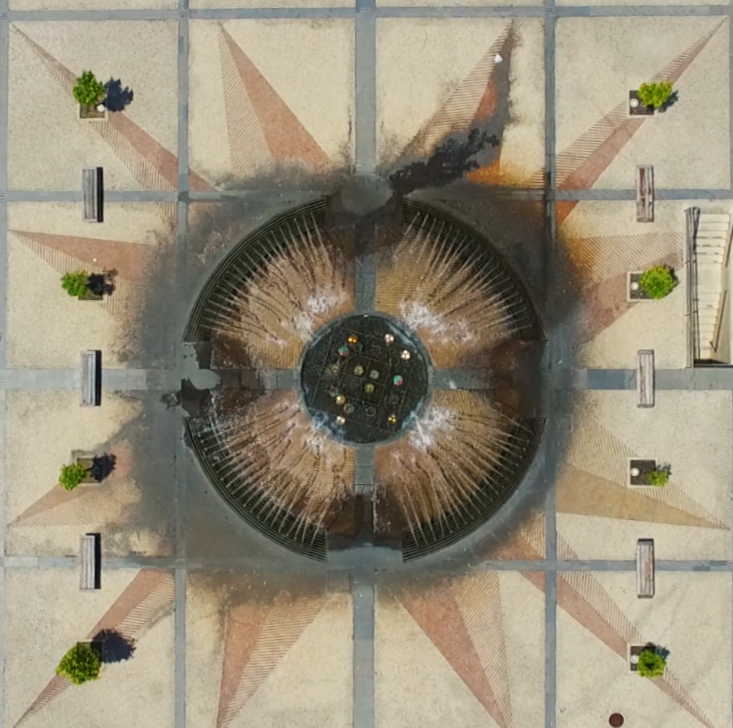

However, the largest Nativity in Portugal is right here in the Algarve. The annual display at the Centro Cultural António Aleixo in Vila Real de Santo António features over 5,800 handcrafted figures and occupies 240 square metres, making it the largest in the country. Since its creation more than two decades ago, the exhibit has expanded into a record-breaking attraction, drawing thousands of visitors each Christmas. Using over 20 tonnes of sand, 4 tonnes of stone dust and 3,000 kilograms of cork, the scene depicts both biblical events and traditional Algarve life – including local landmarks like Praça Marquês de Pombal, the very street where the exhibit is located.

Other nationally acclaimed Nativities include the “natural Nativity” in Sabugal, in the Guarda district. Built entirely from organic materials such as moss, ivy, cork, tree trunks, reeds and sand, this 1,500-square-metre display is set up annually near the town’s castle. It showcases a different kind of craftsmanship, where natural materials symbolise the cycle of life.

A tradition to treasure

While many families have their own Nativity scenes at home, some have turned this yearly tradition into a collector’s passion. The Museum of Évora, within the Church of São Francisco, houses an extraordinary collection of over 2,600 Nativity scenes from around 80 countries. The collection was assembled by Major-General Fernando Canha da Silva and his wife Fernanda, who began collecting in 1999. Since 2015, it has been housed in the museum’s upper gallery above the side chapel, offering a unique insight into how the birth of Christ is celebrated around the world.

Closer to home, José Cortes from Lagos has been expanding his own Nativity since 2011. Displayed at the Centro Cultural de Lagos from late November to early January, Sr Cortes’s creation includes over 275 figurines representing villagers, artisans and biblical characters, as well as 368 animals and 38 miniature buildings. Animated elements such as water wheels, moving carts and blacksmith fires bring the scene to life. His aim is to blend the Nativity story with rural Portuguese life.

A curious guest: the Caganer

Although not traditional in Portuguese presépios, one curious figure has begun to make discreet appearances: the Caganer. This cheeky character, a Catalan peasant wearing a red barretina cap, squatting with trousers down, is depicted defecating. Originating in 17th-century Catalonia, the Caganer symbolises humility, fertility and the earth’s renewal. The name literally means ‘the pooper’ in Catalan. While commonplace in Spanish Nativities, he occasionally pops up in Portuguese scenes as a humorous addition and a nod to our Spanish neighbours.

After visiting the grand Nativity in Vila Real de Santo António last year, I was inspired to create my own Nativity village at home, embracing the Iberian Peninsula’s love for this joyful tradition. Whether large or small, the Nativity scene brings a sense of wonder and continuity to Christmas, reminding Christians of the true meaning of the season. And if you were wondering, yes, my version of the nativity does include the Caganer, just for a touch of Christmas cheer.

Did you know? The Sanctuary of Fátima has a permanent nativity in the nave of the Basilica of Our Lady of the Rosary. It was created by Portuguese sculptor Paulo Neves and erected in 2017.

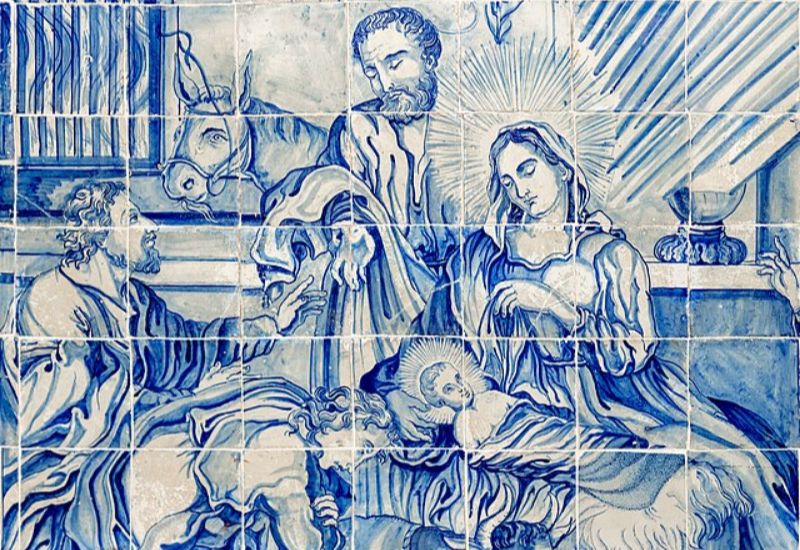

Main photo: Tiled Nativity at The Church of Nosso Senhor do Bonfim by Paul R. Burley (Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license)