The tendency of villages to empty themselves and become ruined shells or second-home dormitories for city-dwellers has been observed in many places and it is particularly prevalent in rural Portugal. In Pedralva, near Vila do Bispo, an enterprising developer has, over the course of many years, successfully acquired vacant cottages and upgraded them one by one to rent out to walkers and individuals.. Pedralva is now branded as a ‘slow village’, i.e. a place to stay for those seeking peace and sustainability.

In Serra da Estrela, the Associação de Desenvolvimento Turístico has identified 12 Aldeias Históricas considered especially attractive – and possibly at risk of dying. Three of them were highlighted in recent years by the UN’s World Tourism Organisation as the best of their type. The aim was to distinguish villages around the world that are genuinely committed to promoting and preserving their cultural and historical legacy, and promoting sustainable tourism. The initiative seeks to “demonstrate that tourism can be a positive force for rural development and the well-being of communities”.

So, keen to be a positive force and in search of one particular Aldeia Histórica, I find myself driving along the N339, stopping only briefly to admire the rugged rock formations, before turning west.

The narrow road clings to the sides of the valleys and the village of Cabeça appears in the distance, but there are tortuous twists and turns before I reach it. Foxgloves, cornflowers and wild lavender crowd over the verges. The area appears to be geologically complex, as I notice upon arrival that Cabeça’s houses are constructed from a mixture of granite blocks and schist.

As a non-geologist, I have to look up schist. It’s a foliated metamorphic rock, displaying a distinct layering of minerals; hence, like slate, it can be easily split into thin flakes or plates. Schist, I read, contains minerals such as quartz, mica and graphite, which can result in interesting variations of colour. The rust-coloured surfaces I see on some of Cabeça’s buildings suggest the presence of iron oxide. In any case, it’s beautiful as a building material, even when mixed with granite.

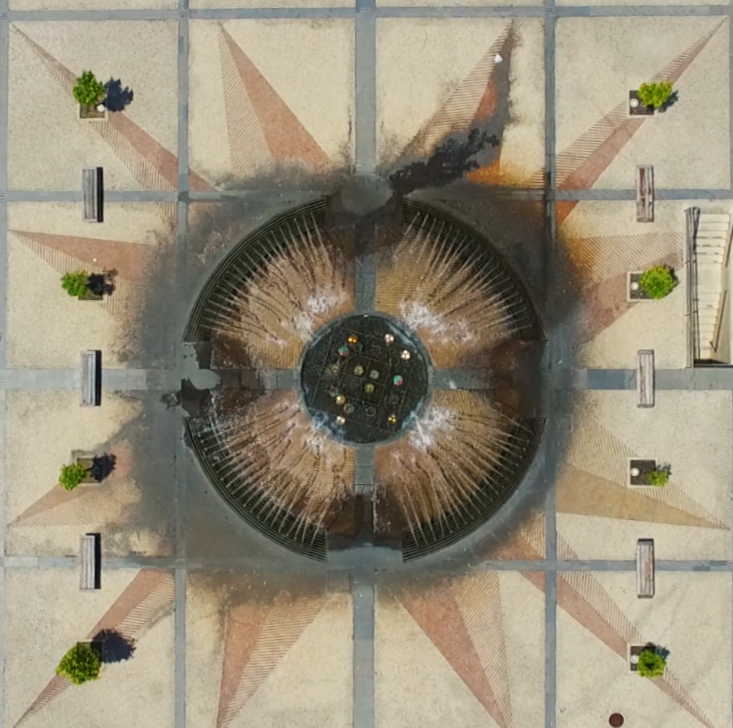

The road winds on through Vide past walls colonised by tiny Sedum rock plants. After a series of hairpin bends, Piódão comes into view and I park. One of the 12 villages Piódão, is almost entirely built of schist. The exceptions are two small chapels and the rather grand church, all rendered in dazzling white. On the slopes below the village are terraced fields which supply the residents with fresh fruit and vegetables. Further on, there’s a small museum, however Piódão receives very few visitors, as the photo of the church frontage demonstrates.

I wander along the street past a tumbling cascade of spring water and turn up towards the chapel dedicated to São Pedro. The streets and alleys are densely packed and many of the buildings are taller than is usual in a Portuguese village – some are four storeys. There are a couple of small restaurants – at least these have clientele clearly enjoying the local fare. Nearby stands the 18th-century Igreja Matriz, with a most unusual west front: four cylindrical turrets each crowned with a plain conical pinnacle.

The schist walls of Piódão are constructed with admirable care and accuracy, each piece perfectly aligned with its neighbours and I wonder about the mortar bedding as the joints are all open. Almost every door I see is bright blue.

One of the signboards points the way to several recommended walks in the area, the Serra do Açor. Promoting these is one measure hoped to attract more visitors to the area. Regrettably, I cannot stay longer, and I leave this possibly unique place to return to the plain white walls of the Algarve.