How modular homes are transforming the Portuguese countryside

“Head to the cemetery and I’ll be the last one alive before you get there,” was how Prof Alex de Rijke explained where to find his plot of land on the edge of São Teotónio.

The abandoned ruin and farmland on the southwestern coast of Alentejo is perhaps an unlikely place to find one of the world’s top architects specialising in wood – a professor of timber architecture at Delft University in the Netherlands. But residents of Odemira are no longer surprised by the range of interesting people from all over the world who have discovered a hidden corner of Portugal and want to make it their home. And those living in rural Portugal are no strangers to the many wooden structures now replacing ruined houses as foreigners move to rural areas, buy old, abandoned plots of land, and, with a shortage of builders, look for innovative solutions.

A rural renaissance

For decades, people have been abandoning the countryside for the cities or to travel abroad, leaving land untended and a lack of labour. The speed, cost and convenience of modular wooden housing is driving a construction revolution in Portugal and across Europe, not least because it is sustainable, renewable and locks carbon into the structure of buildings. While flights contribute 2.5% of global carbon dioxide emissions, the construction industry accounts for almost 40% of the total. Wood building can dramatically decrease that as forests can be constantly regenerated.

“This is where the house will be, above our heads, on stilts,” Prof de Rijke explained, as we walked down a track overlooking the floodplain and a bubbling brook where he plans to plant trees and grow vegetables. But this is no new-build. The British Stirling-prize-winning architect designed and built a flat-packed house twenty years ago for an architectural exhibition in Oslo.

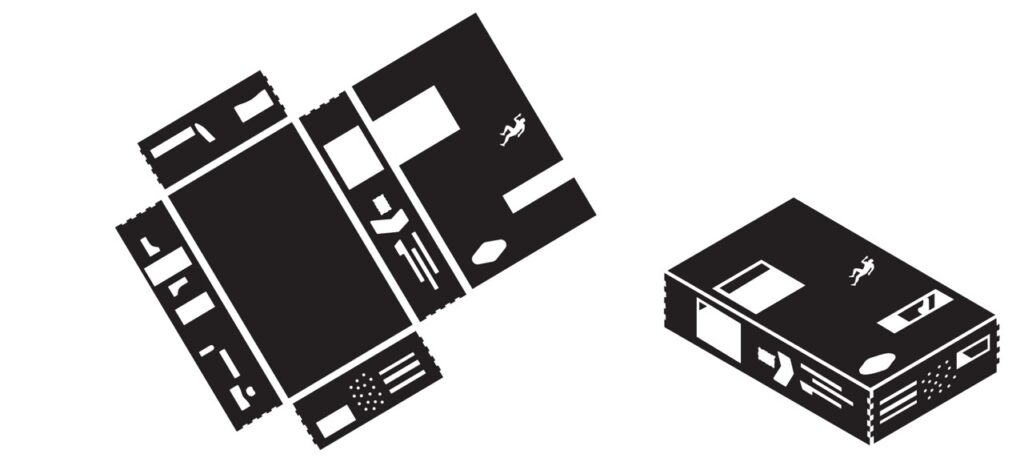

Flat pack: the Naked House was created to be transported easily and then assembled on site out of Cross-Laminated Timber (CLT) panels

The science of strength

The ‘Naked House’ now sits stacked up in a field under a tarpaulin in São Teotónio, waiting for permission to be assembled and mounted among the cork oak trees on his hillside.

It was an experiment built from Cross Laminated Timber (CLT) panels – “a bit like a jumbo plywood or scaled-up plywood” material, which has transformed the wooden house industry. “Plywood is veneers, thin veneers, and so is this. You take a tree and you rotary cut it like a pencil being sharpened, and then those shavings are glued together in different directions, and that makes it strong.”

Thicker layers of wood pressed together can create beams longer, stronger and lighter than reinforced concrete, or the panels used for the Naked House, which are 13 m long by 3 m wide. The windows, doors and skylights were cut out in various shapes and made into furniture. “I basically cut the furniture from the walls. So think that a table cut from the wall becomes a window which lights the table, so the off-cut is the furniture, and therefore there’s no waste,” he explained. “It fits together like a jigsaw puzzle. It’s just a kind of geometry game.” A running man silhouette lets light into the toilet: “That’s me as a bathroom skylight.”

The efficiency of modular construction

Alex de Rijke is just one of the many international arrivals to Portugal opting for flat-packed or modular wooden houses. One of the biggest names in Portugal is Jular – a family firm whose luxurious Tree House models adorn the sand dunes of Comporta and whose giant factory in Azambuja, north of Lisbon, is a constant buzz of carpentry tools. “We have been in the modular industry for around 25 years. In the beginning, it was like preaching in the desert: nobody was listening to us. But in the last ten years, it has been like a growing tide, and we cannot stop it,” Amaro Santos, production manager at Jular Madieras, told me when I visited.

“This is the first floor of a kindergarten,” he explained, as we wandered the upstairs corridor of a 45-metre long building already fitted in the factory with windows, doors, wall and floor insulation, electrical wiring and plumbing. “We break it into 15 different sections, or modules. Each module is about 3.5 m wide and 4 m high, so we have to have special lorries. They’re going to leave the factory 95% finished. It’s much cheaper for the client. I can manage quality much better here, working under one roof … with the labour shortage … the end result is a much higher quality.” Carpenters and electricians don’t have to spend weeks on site, and the buildings can be installed on pre-placed giant metal screw foundations in a day.

In another part of the factory, a two-bedroom family home is being readied for transport to Aljezur – sometimes the modules are delivered with fully fitted kitchens and furniture already inside. “One of the main advantages – besides the sustainability – is the certainty that the customer is going to have a house delivered on budget, on time, and with quality. It’s not easy to have that result with regular and traditional methods of construction.”

Building the future

Jular produces around 200 modules a year and half of their clients are foreigners. Amaro says that while there are no official statistics for the proportion of wooden houses being built in Portugal, it’s constantly increasing. “There are a lot of people entering the market right now, and there is room for everybody, because we think this is the way to build in the future. It’s not an option not to go this way.”

But the wood isn’t Portuguese. Jular buys and transports most of its raw material from Finland, as the vast eucalyptus forests planted across Portugal aren’t suitable for building – they’re pulped for paper or processed into pellets for biofuel. Scandinavian and northern European countries have the forests required for this industry: 40% of Europe’s wooden houses are produced in Estonia.

Sweden has been building wooden houses for generations and has been a leader in using cross-laminated timber (CLT) and other fabricated wooden materials, which are stronger and lighter than reinforced concrete. In 2013, the first residents moved into Strandparken, a residential park with two eight-storey apartment buildings with everything above ground – including the elevator shaft – made completely out of wood. “Those were the first real or massive CLT buildings in the Stockholm area … and they kind of revolutionised the Swedish construction scene,” said Sandra Frank, whose development company Arvet only builds in wood. “About 36 to 38% of the total global carbon dioxide emissions come from construction sites.” She explained that cement production alone contributes 5%, which is twice as much as the global airline industry.

In Sweden, there’s a word for flight shame – flygskam – a movement urging people to avoid flying for environmental reasons, but despite the huge impact of the construction industry, there’s not as much public pressure for change.

But critics question the sustainability of cutting down forests for wooden housing.

“I called the factory that was making the CLT and I asked them how much time does it take for the Swedish forest to grow the 2,000 cubic metres of CLT which each (eight-storey) house contains. And they said 44 seconds,” said Sandra. A century-old law in Sweden ensures every tree cut down is replaced by a new one.

“Today we are planting about four trees for each tree taken down … and now we have more than double the amount of forests than we had 100 years ago.”

She described concrete and steel as “ending materials”, which are also taken from nature: “if we can start using growing materials instead of ending materials, that would be a lovely thing. We actually store carbon for as long as these buildings are standing.”

Fire risk is also a concern for wooden houses – something Alex de Rijke is well aware of, after a large wildfire in 2023 nearly reached his land in São Teotónio.

“Wood is much better behaved in a fire than steel. Steel collapses suddenly at 500 Celsius, but engineered timber just chars and protects itself, just like these cork oak trees here,” said Alex. And it’s something he says mortgage companies and insurers are starting to understand. New policies encouraging carbon capture and increased understanding of the impact of building is leading the big construction and architecture companies to build in wood.

A wooden revolution

“It’s a really exciting period, I think. To be an architect and an engineer and a builder right now is to be taking part in – and possibly helping in – a revolution. “Revolutions take a little bit of time. There’s cutting edge and there’s bleeding edge. The bleeding edge goes out first and does all the real experiments. Then there’s the cutting edge, who know what to do with it, because someone else has done the bleeding bit. And I’m somewhere between the two,” explained Prof de Rijke.

As the global construction industry faces mounting pressure to reduce its massive carbon footprint, the transition to modular wooden housing represents a vital shift from depleting natural resources to utilising regenerative materials. By combining factory precision with the natural carbon-capturing properties of timber, this movement offers a solution that is as much about environmental stewardship as it is about architectural innovation. While the “revolution” is still unfolding, the success of pioneers in Portugal and Scandinavia suggests that the future of our homes lies in a sustainable “geometry game” that benefits both the resident and the planet.

Alastair Leithead is a former BBC foreign correspondent now living in Odemira, where he and his wife have just opened @vale_das_estrelas, or the Valley of the Starseco-luxe lodge. He blogs at Off-Grid and OPEN in Portugal and podcasts Ana & Al’s Big Portuguese Wine Adventurein all the usual podcast places.

Main photo: Hastings Pier: Prof Alex de Rijke’s firm dRMM won the UK’s top architecture award – the RIBA Stirling Prize – in 2017 for the regeneration of Hastings Pier in East Sussex. The pier was rebuilt after a fire © dRMM Jim Stephenson