As a lover of seafood, I was alarmed by the environmental and health concerns highlighted in the Netflix documentary Seaspiracy. After being invited to Pescalgarve on the Ria de Alvor, I was determined to investigate aquaculture in the Algarve and decide for myself whether I was a happy consumer.

The purpose of my trip to Pescalgarve was to discover for myself the truth behind the farmed robalo (sea bass) and dourada (sea bream) reared here. What I found was a fascinating project that not only delivers delicious, fresh fish to restaurants and supermarkets but is also involved in a forward-thinking sustainability project that aims to create aqua diversity and restore seagrasses and sea cucumbers, all funded by huge EU grants.

Something fishy

I turn off the N125 at Odiáxere towards the Alvor estuary, where the saltwater is naturally replenished by the tide, providing ideal conditions for a number of aquacultures. I have been told to arrive at 9 am to witness the’fishing’ of the dourada, which grow in clay tanks metres from the sea.

Crossing the railway tracks, I pull up outside some large wooden gates which look more like the entrance to a grand villa. They open to allow me to drive up a long track past an old dwelling and up to the small factory. I am warmly met by owner António Viera, a serious and thoughtful man who is certainly not what I was expecting. I enter a meeting room to view a presentation on a large wall-mounted screen. António has more of the air of an academic and I soon find out why. A marine biologist, he began researching marine life in 1987 before joining the Portuguese Institute for Sea and Atmosphere (IPMA), which operates the Estação Piloto de Piscicultura de Olhão (EPPO), a primary research centre for aquaculture, marine biology and sustainable fishing in the Algarve. Located in the Ria Formosa Natural Park, this facility focuses on fish reproduction, feeding and monitoring bivalve beds, functioning as a key hub for scientific, academic and industrial training.

I stare at the screen, which shows an aerial view of the farm. With its tanks adjoining the Ria de Alvor nature reserve, it is more like a natural wonder than an industry. António started the concession in 1989, leasing the land from the Portuguese Environment Agency. The video moves on to show the fish and António points out the markings of the dourada, which show a violet hue in sunlight and a yellow band between the eyes, reflecting their diet. Dourada are omnivorous, eating worms, crustaceans, and algae. Each tank is pumped by an aspirator, which injects air directly into the water stream, aiding aeration and surface movement, providing oxygen to the water, and is adjusted based on the water’s temperature at any given time. Water molecules vibrate more with heat and inhibit gas absorptions, so the water has to be closely monitored and oxygen injected when it gets below a critical level. Just like us, a fish’s health is dependent on receiving good-quality air. If the oxygen levels are not adequate, it would be equivalent to a human living in smog.

The health of the fish also depends on introducing beneficial bacteria into the tank’s sediment. Nature helps them, as the salt marshes act as a biofilter, removing the nitrates and ammonia and leaving behind the good stuff! Algae and worms act as natural biofilters that absorb excess nutrients and break down organic waste. António explains: “You don’t get a strong fishy odour here because there is a good cleaning cycle. The fish, in turn, keep the bottom of the tanks aerated as they dredge for worms.” Integrating the fish farm into a balanced ecosystem is often referred to in scientific circles as Integrated Multi-Trophic Aquaculture (IMTA). A good way for non-scientists to view this approach is to think of the different species in the food chain as nature’s cleaning crew.

This really is turning into a science lesson!

So what about the antibiotic conspiracy?

Good bacteria repel the bad, so having a healthy microbiome ensures healthy fish and eliminates the need for antibiotics, which have become such a bad word in fish farming. I ask António if it’s something we should be worried about. Apparently not. In Portugal, the legislation to stop antibiotics from entering farmed fish is governed by stringent European Union (EU) regulations. These EU rules are directly applicable in Portugal and prohibit, or strictly limit, the use of antibiotics in aquaculture. “We sell directly to Intermarché and they, along with other buyers, test for antibiotics. We are also visited by vets to check on our processes every two years. If they found it in our fish, it would ruin us. We focus on rearing healthy fish through our traditional estuary system with continuous monitoring to guarantee animalwelfare and superior quality.”

Pescalgarve have had only one incident in which they had to use antibiotics to save a tank of sea bass (robalo). After that, they leave the fish to grow before testing to ensure all traces have decomposed in the fish. EU legislation has a specific formula for calculating the time required, which depends on the water temperature. In fact, Pescalgarve have decided to phase out sea bass, which require more supplements to keep healthy. Another consideration, in terms of animal welfare, is that sea bass are hunters, so it is difficult to give them the stimulation necessary for their mental health in a tank.

Fishing for quality

António’s son, Leonardo, has just returned from supervising their small team of ten and urges me to come and see them ‘fishing’. Leonardo Viera is an impressive young man; while António is a Portuguese marine biologist, his mother is a German doctor. This means he is well- educated and extremely knowledgeable and passionate about the subject of fish! As we drive to one of the tanks, he explains that he studied business engineering in Germany before joining Mercedes. When the pandemic hit, he returned home and wrote a thesis on his dad’s company, which explains his extensive knowledge of aquaculture. The business was hit hard by COVID, so he decided to return to his roots, joining the family business as commercial and operational director.

Leonardo talks me through the life cycle of their fish, which bizarrely starts in France. Unable to breed successfully, Pescalgarve buys around 100,000 juvenile fish per tank, totalling around 400,000 fish per year. This equates to an investment of € 108,000 (€ 27,000 per tank). These fish, which are around 180 days old and weigh 5 kg, are placed in a tank where around 20% will die, but the rest will be fed fish pellets to ensure they grow healthily. Leonardo shows the pellets to me; they look exactly like a pellet you would feed your goldfish, but contain a surprising variety of ingredients, including garlic, which has antibiotic properties, fish meat, fish oil, and scraps from olive oil production. Floating feeding stations allow them to check whether the fish are feeding properly. Fish are regularly taken from the tank and analysed to check their health.

After approximately two years, they catch half the fish and let the rest grow to a larger size, which is more profitable to sell. I stand with Leonardo on the bank to watch the spectacle of the fish being taken from the tank. Prior to being caught, they are not given food, so there is no residue inside the fish. A crane places a small wooden boat in the water, so you might think you are watching a local on a lazy weekend fishing trip. The boat circles, with the net trapping all the fish, which are then tipped into a giant metal bucket with holes to drain the water.

The fish are then immediately put into an isothermic box with ice-cold water, which gives them hypothermic shock and kills them. This method causes less stress or damage to their scales, and it keeps them lubricated.

We follow the truck that takes them to the small packaging plant, where they need to stay below 2oC. A machine sorts the fish by size and weight, and the ‘fishermen’ from earlier now pack them into boxes. Leonardo explains that a truck will arrive around lunchtime and some will be in a market in Lisbon by midnight and in Porto by 6 am the following morning. They have an annual production of 100-120 tons and custom sizes ranging from 300g to 2000g, delivering to restaurants, markets and shops, while some even end up on plates in Madeira. Pesgarve sells to Intermarché in Lagos when they have the origines promotion, which supports local producers. Ask the vendor for the origin to verify it’s from Pescalgarve.

Leonardo explains that they provide a vital public service, as in summer, the ocean can’t keep up with the demand from tourists. He assures me, however, that the flesh of their fish tastes identical to ocean-caught fish.

A natural partnership: fish, algae and sea cucumbers

When Leonardo asks me if I want to meet the PhD student working on a project, I eagerly agree. This trip to a fish farm is taking on a whole new dimension I was not expecting. João Sousa from IPL (the Polytechnic Institute of Leiria) is in the fourth year of his PhD, which involves studying the reproductive stage of sea cucumbers. He leads me into a building with a computer for his work, then into a series of tanks. The odour is horrific. “The smell is a little funky,” he grins. “But you get used to it.” Sea cucumbers release saponins, chemical compounds with a strong smell and taste.

João talks about sea cucumbers like a proud parent, showing me a large specimen he is responsible for. The aim of the research is both altruistic and commercial. Sea cucumbers in the Atlantic Ocean are in danger primarily due to intense overfishing driven by high demand for luxury seafood in Asian markets, leading to widespread population declines, particularly in the Mediterranean and Northeast Atlantic. Unregulated and illegal harvesting, combined with slow reproduction rates, has resulted in severely depleted stocks.

The AQUADIVERSIFY project is a pioneering initiative aimed at revolutionising how we produce seafood by bringing a natural, balanced ecosystem to commercial farming. It is a collaborative effort between industry leaders and scientific powerhouses, including CCMAR, GreenCoLab, and Mare-PL. The project is supported by the European Union and programmes like COMPETE 2030 and Algarve 2030. Led by Pescalgarve, this three-year project is introducing a farming method that is currently unique in Portugal. At its core, the project is about teamwork between species. Instead of farming just one type of fish, AQUADIVERSIFY integrates three different levels of the ocean’s food chain:

Fish: building on the company’s history of producing high-quality bass and bream

Algae: plants that help balance the environment and serve as a food source for the dourada

Sea cucumbers: nature’s “cleaners” that help maintain a healthy ecosystem

By combining these three, the project creates a more efficient and sustainable production system that mimics the natural cycles found in the wild.

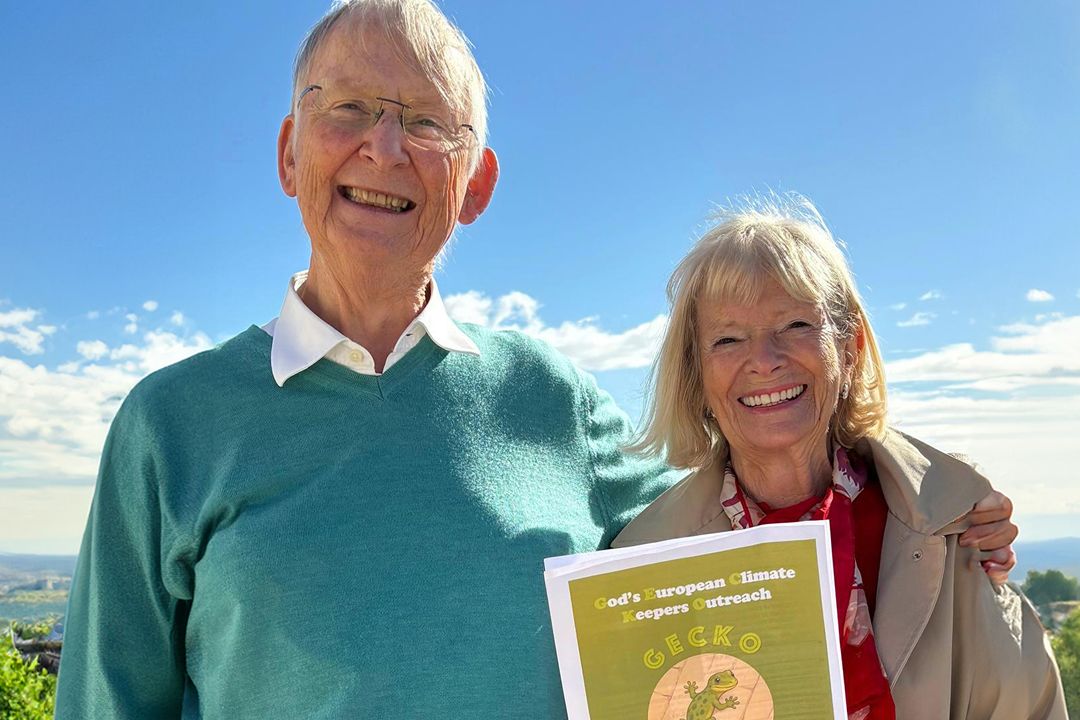

I realise that this aquaculture isn’t just about farming; it’s about innovation and sustainability. The project aims to achieve several major breakthroughs, including establishing a commercial-scale model that has never existed in Portugal before. By using natural systems in watercourses, the project significantly improves the environmental impact of traditional farming. The goal is to create high-value-added products that are both profitable and sustainably sourced. Through a massive €1.5 million investment, the project is generating strategic knowledge to help the entire national aquaculture sector grow.

João is realistic when he tells me, “It’s all about how we can eat protein in a sustainable way as we move into the future. The reality is that unless it has a commercial value, businesses won’t embark on the journey, so we are using creative ingenuity to create a profit but in a sustainable way.” His research into how to successfully grow sea cucumbers in captivity will mean that they can return some to the ocean as well as sell them for commercial gain.

A hopeful view of the future

As I say my farewells to João and Leonardo, I can’t help but feel incredibly uplifted by my day of scientific discovery. I came to find out if I felt happy about eating farmed fish. My resounding conclusion was yes! But not only that, my slight despondency about consuming farmed food in general, with so many negative messages, was transformed by this innovative project.

If you are as fascinated by this project as I was, Pescalgarve will start tours in April 2026, benefiting future tourism and offering a new local activity for families and schools.

Who knew that the peaceful banks of the Alvor estuary were hiding this forward-thinking project that aims to reframe how we consume in the future? Under the brand name Pescalgarve and the inviting slogan “taste the ocean”, this project is proving that we can enjoy the best the sea has to offer while actively protecting its future.

+351 912 267 797