Arrifana, nestled on the south-west coast of the Algarve, a haven sheltered from the prevailing northern winds, is more than just a picturesque fishing village; it is a living testament to centuries of human ingenuity, resilience, and, more recently, rapid transformation. Its bay, an integral part of the Natural Park of Southwest Alentejo and Costa Vicentina, boasts a vibrant ecosystem teeming with marine life and breathtaking rock formations. But beyond its natural beauty, Arrifana holds the tales and secrets of many years of history, stories now being unearthed and preserved by individuals like anthropologist Vera Abreu.

When I met Vera Abreu, a cultural anthropologist, we immediately found a common passion. We both love to tell the stories of the Algarve’s social history. While I do this through the pages of Tomorrow, Vera does it through a camera lens. The result was her poignant documentary, aptly titled O Inverno é muito longo e o verão pode não dar para tudo (The winter is very long and the summer may not give everything).

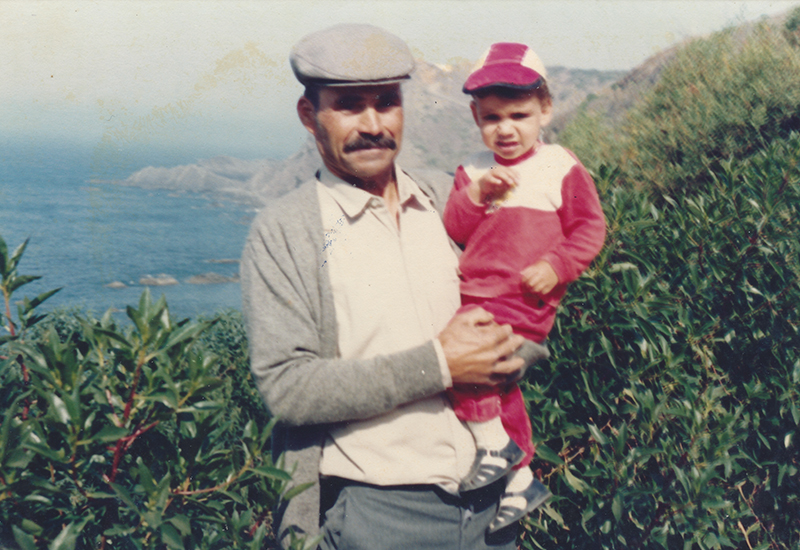

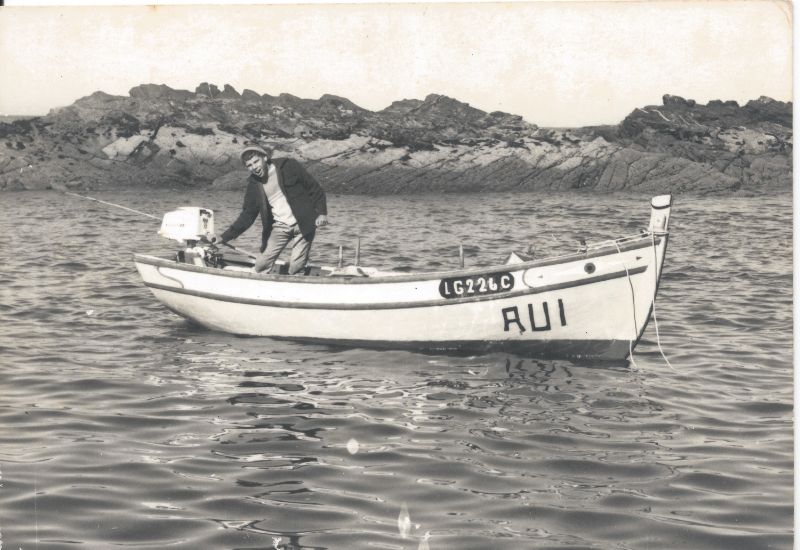

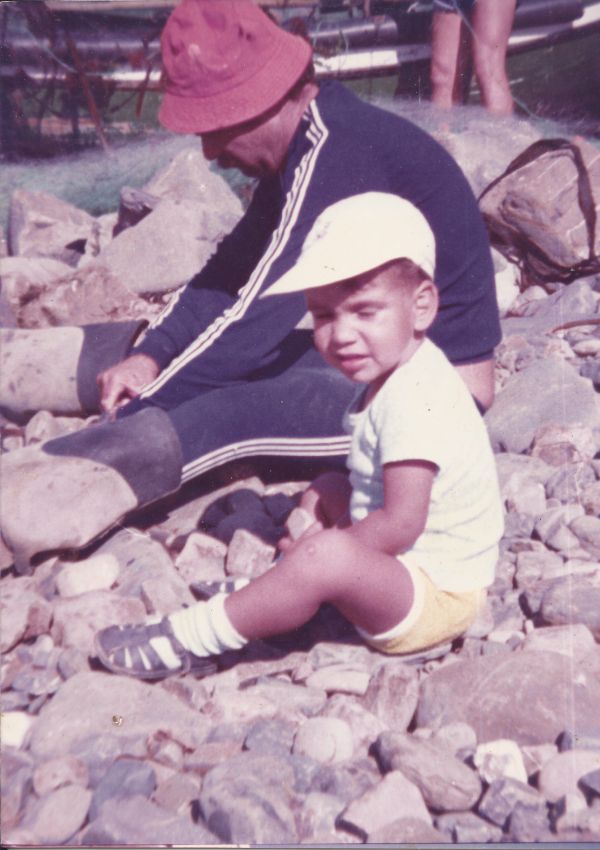

While studying for a master’s in Visual Anthropology from the University of Lisbon, Vera dedicated her line of investigation to the nuanced shifts in coastal communities. Choosing film as her medium for her dissertation, Vera embarked on an ambitious project to investigate “How the skills of a job or a practice are passed down within the family”. Her journey led her to the heart of Arrifana’s fishing community, focusing on a multi-generational family – the grandfather Ti Raul, his son Rui Arez (known as Giló), and grandson Eugénio – who represented a continuous line of fishermen.

This film represents a two-year labour of love involving extensive fieldwork, interviews, and time spent at sea with the fishermen. An invaluable piece of research, it chronicles not only the ancestral arts of fishing but also the profound impact of tourism and globalisation on a way of life that once defined Arrifana.

A harbour of history

Arrifana’s history stretches back millennia, with traces of human occupation by fishing and gathering communities dating to around 10,000 BC. Sedentary tribes later settled in the region throughout the Stone and Bronze Ages. Vera Abreu’s anthropological study delves into how this once self-sufficient and almost insular community functioned. She explains that Arrifana was initially a seasonal settlement, where fishermen would come for summer work before returning to their villages. These early fishermen, such as the generation before Ti Raul, were primarily farmers, with fishing serving as a supplement to subsistence farming. However, the economic allure of the sea was significant. Vera explained to me, “When they came to fish in Arrifana, they earned more in three months than all year.” In a time when physical money was scarce, and an economy of exchange prevailed, fishing offered a valuable commodity. Fishing became a way of earning real money during the summertime, complementing a life where families had pigs, chickens and allotments to grow vegetables, and swapping goods with neighbours.”

Ti Raul: local legend and guardian of history

The documentary begins with the breathtaking seascapes of the area with a soundtrack of gulls. We meet Ti Raul as he wades through shallow waters to a rock pool where he pits his wits against an octopus that is hiding under a rock. He announces, “If you ask anyone around here who is the oldest fisherman, they will tell you it’s me.”

Born in 1925, Ti Raul is celebrated in the municipality of Aljezur as the guardian of the memory of the fishermen’s settlement in the bay. As he says sadly, “My colleagues with whom I went to sea and my mates from here are all dead.” Vera Abreu’s film uses his personal and family life experiences to trace the evolution of Portinho da Arrifana and its fishing community.

Ti Raul’s memories offer a vivid portal to a bygone era. “I was born in Aljezur. My father had a few small houses. He sold them later. We were six siblings. Five boys and a girl, but I was the only one who leaned towards the sea. After I was married, I got a fishing licence and went to sea.”

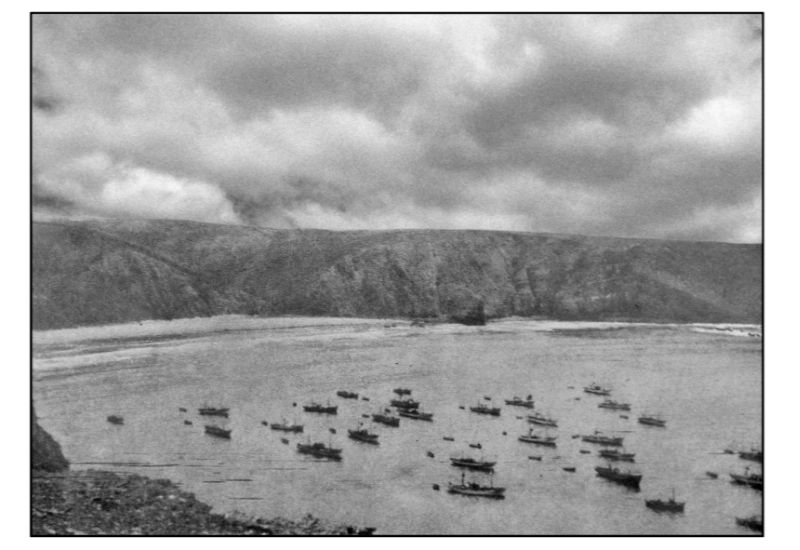

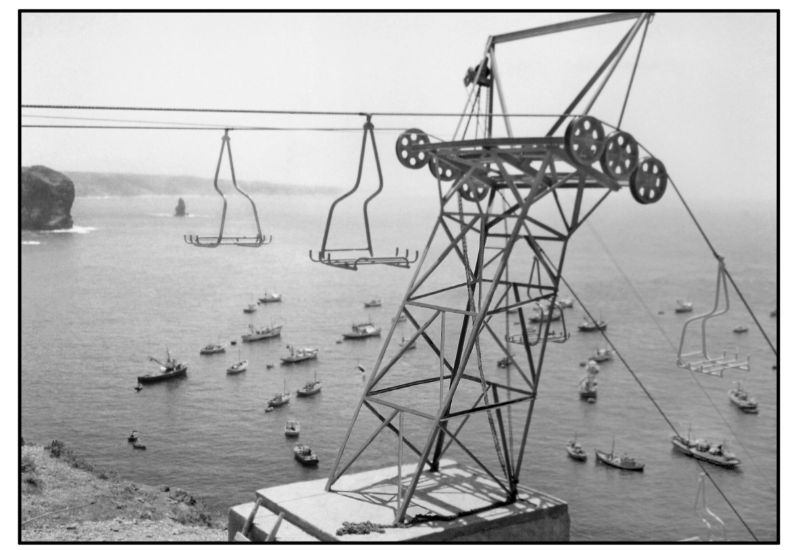

He recalls a time when a fishing company owned by a local businessman, Sr. Mendes, employed men to work on the trawlers during the summer months. They came from distant towns like Olhão, Setúbal, Vila do Conde and Vila Nova de Milfontes, attracted by the abundance of fish and lobster. The landscape at this time was very different. The documentary shows archive photos of Arrifana when there was no harbour, Ti Raul just recalls a few places to store the smaller boats, but the larger ones had to be pulled out of the water to protect them from storms. Remarkably, there was also no road at this time, only a cable lift driven by an engine and with baskets to pull up the fish. He recalls that they would row in small boats to Atalaia or the river mouth at Amoreira beach to line fish for cod.

Some days they would leave Arrifana mid-afternoon and sail to drop nets, returning at 10 am the next day. “It was hard work. I remember the fish would be carried by donkeys driven by women who took them to Aljezur market.”

Ti Raul explains that they used to only fish between Easter and September. They started to build little houses to stay in; in those days, there were no property taxes. The dwellings were basic, but over the years, they refurbished them and started to stay for longer periods.

Another fisherman in the documentary, called Armando, told Vera how fishermen would safeguard the locations of abundant fishing spots, protecting their learned knowledge for finding fish. He recounts, “The comrades of a vessel could not say where they had caught the fish, in order to preserve the intelligence of the fisherman to catch the fish.” This secrecy was crucial for survival and maintaining an edge in a challenging profession.

The requirement for all fishing buoys to be identified today stands in stark contrast to the past, where secrecy was paramount. Armando expresses a profound sorrow over the erosion of these traditional practices. He laments the advent of modern technology like GPS, which, while aiding navigation, has, in his view, diminished the inherent skill of the fisherman. “Today, there are no good fishermen.” He informs Vera that now other fishermen will simply find his pots to know where to leave theirs, and that the skill of fishing is dead. He further criticises the allocation of subsidies to the newcomers rather than to the experienced fishermen who possess “life doctorates” – the wisdom gained from a lifetime at sea.

Apprenticeship in a changing world

Vera Abreu’s core anthropological inquiry revolved around how fishing skills were historically transmitted within families. Ti Raul’s life, as depicted in Abreu’s documentary, is a bridge between the traditional, arduous life of a fisherman and the rapidly modernising present. He discusses how the process is now like “paradise” with mechanised distribution and invoicing.

Her research revealed a deeply ingrained process: “I came to the conclusion that your knowledge normally comes from the inside of a relation between father and son, or grandfather, son and grandchild, or a master and beginner, like an apprenticeship. This intimate, daily interaction means the knowledge becomes ingrained in your body, absorbed through constant observation and repetition. Unlike theoretical learning, this hands-on, embodied knowledge, where the gesture is kept in his body, in his hand, is crucial for professions like fishing.”

In her documentary, we see two men, one is cutting up fish and the other mending nets. They laugh as they tell Vera, “It’s all about learning from the elderly. Your fathers and your grandfathers.”

Eugénio, Ti Raul’s grandson is a third-generation fisherman and exemplifies this transfer of knowledge. He still employs traditional azimutes (landmarks on land) passed down from his grandfather and father for navigation, even as he utilises modern GPS technology. This blend of ancient wisdom and contemporary tools exemplifies the juxtaposition of past and present.

However, Abreu observes that this traditional process of knowledge transfer is now at risk of ending. She notes that, “The young generation is not so much motivated to these kinds of professions. The allure of longer educational paths, university, cell phones and the internet act as powerful distractions, drawing younger generations away from the demanding life of a fisherman.”

While Eugénio’s young daughter, whose mother owns the local pharmacy, still enjoys fresh fish caught by her grandfather and boat tours with her father, Vera doesn’t believe she or her sister will become professional fishermen. This signifies a crucial break in the chain of traditional apprenticeship.

Despite this trend, Vera points out that there are exceptions, particularly in nearby Sagres, where some younger generations are returning to their roots. These fishermen, aged 35 to 40, are finding that they earn good money and can live well from fishing, e.g. catching valuable octopus, despite the arduous nature of the work, such as leaving at 3 am for sardines. This suggests a complex future for fishing, where a return to tradition might be driven by economic opportunity, but the inherent draw of a simple, local life for a young generation might be eclipsed by modern careers and digital distractions.

The tide of tourism

Vera Abreu’s personal journey mirrors the dramatic changes that have swept over the small village of Cascais, near Lisbon, where she grew up. She recalls her mother buying fish directly from the fishermen’s boats in Praia do Peixe in Cascais, which was then a fishing village. Her first visit as a 17-year-old in 1977 to Arrifana, after the 25th of April revolution, revealed a place where “Everything was very simple. So you didn’t see the buildings that you see now.” Over the decades, through her regular visits with her husband and children, she witnessed the transformation first-hand, from purely Portuguese tourism (initially from Lisbon and Porto) to an influx of visitors from Spain, France, and, later, permanent residents from Britain and Germany. This evolution, she concludes, “Has to do with the globalisation, leading to a multicultural movement with people from Israel, Italy, South America, America, Australia and New Zealand now making Arrifana their home.”

The most significant change, as documented by Abreu and corroborated by other accounts, is the rise of tourism. After 25 April, people began coming to Arrifana specifically for the beach, and fishermen quickly adapted by renting out their houses. This small-scale rental market for Portuguese families eventually paved the way for the beginning of the surf industry in the 1990s.

Eugénio, Ti Raul’s grandson, embodies this pivot towards tourism. As a young lifeguard, he formed friendships with surfers from Lisbon and abroad, recognising an emerging opportunity. While still a professional fisherman, Eugénio diversified, buying a boat and launching a new enterprise that blends his ancestral knowledge with tourist activities. His business now offers a range of experiences: fishing trips, combined fishing and tours, sunset cruises, and surf trips to known wave locations. He not only rents surfboards and provides water sports but also offers scenic tours where he shares the traditional navigation secrets and fishing spots learned from his grandfather and father. Even his mother contributes, making fish stew for tourists. As Vera notes, “Eugénio has skillfully transformed his ancestral knowledge to a tourist activity, supplementing his fishing income and ensuring his family’s livelihood in a changing economy.”

The physical landscape of Arrifana has also been reshaped by tourism. What were once simple fishermen’s dwellings for storing nets have been renovated and are now regulated, requiring local accommodation permits and inspections. The entire hillside, historically granted to old fishermen for their homes, now sees these properties rented out. Vera observes that “Nowadays, the houses mostly belong to foreigners. You can count on your fingers the fishermen who still have their houses. And even if they have, they don’t live there. They rent it during the summer and earn their money for the winter.”

The documentary also explores the boom in surfing, which created new dynamics. Arrifana’s port still boasts a strong fishing community with 18 vessels operating with around 25 active fishermen. The fishermen’s daily hustle now coexists with the surfers, as they share the rhythm of the waves and tides. This coexistence is not without its challenges. “Fishermen are now angry because the surfers come down to the harbour because there is a spot where the waves are very good, leading to the installation of a barrier at the harbour entry,” Vera tells me. At one point in the film, Ti Raul stands above the beach looking down on the surf schools with contempt. He tells us that they have taken over the beach with swimmers regularly being hit by boards and the lifeguards powerless to intervene. Interestingly, he also observes that his generation only went to the beach for festivals and fishing and never used it for recreational purposes.

Even traditional festivals have evolved. The Blessing of the Boats festival, initiated to provide a religious focal point and divine protection for fishermen, their vessels and their income from the sea, has evolved from its devotional roots into a more social gathering centred on food and drink.

Ti Raul: a brand symbolising changing tides

In a powerful symbol of Arrifana’s evolution, Ti Raul’s name, once synonymous with a humble, skilled fisherman, has now become a brand. His family, particularly through Ti Raul’s great-grandchildren’s tourism ventures, celebrates Ti Raul’s legacy with an active Instagram page (@tiraul_arrifana). This transformation encapsulates the changing tides of Portugal. Ti Raul, the fisherman, a living link to ancient traditions, now lends his name to a modern brand, symbolising old ways diffused with contemporary tourism.

The story of Arrifana, as revealed through Vera Abreu’s work, is a microcosm of a global phenomenon. It highlights the delicate balance between economic development and cultural preservation, between embracing new opportunities and safeguarding the legacies that define a community. As the tides continue to turn, Arrifana, much like its resilient fishermen, must navigate the future, striving to hold onto its soul while adapting to the ever-changing currents of the modern world.

Thanks to Ti Raul, Rui, Eugénio for their help and cooperation with this article.

Photos courtesy of: José Marreiros, Carlos Santos, Família Arez, Roberto Luz, Vera Abreu

Read a previous article about Eugénio: tomorrowalgarve.com/jun-2024-a-man-for-the-people/