In this series, we investigate the historical figures who have shaped Portugal.

At the dawn of the 16th century, through pioneering navigation and brilliant seamanship, Portugal reset the frontiers of the known oceans. At the same time, through piracy and unmitigated terror, it paraded in all its horror the dark side of conquest. One man was behind both milestones: Vasco da Gama.

Since the pioneering oceanic exploration directed by Henry the Navigator, Portugal had continued to push forward the frontiers of the seas, and Bartolomeu Dias had been the first to round the Cape of Good Hope in 1488. Having done so, he returned to Lisbon with the news that the East – however vaguely defined – was at last accessible by sea. After Manuel came to the throne in 1495, exploration was pursued with renewed vigour. To lead the mission to reach the East and return, he chose, for unknown reasons, the young, relatively obscure courtier, Vasco da Gama.

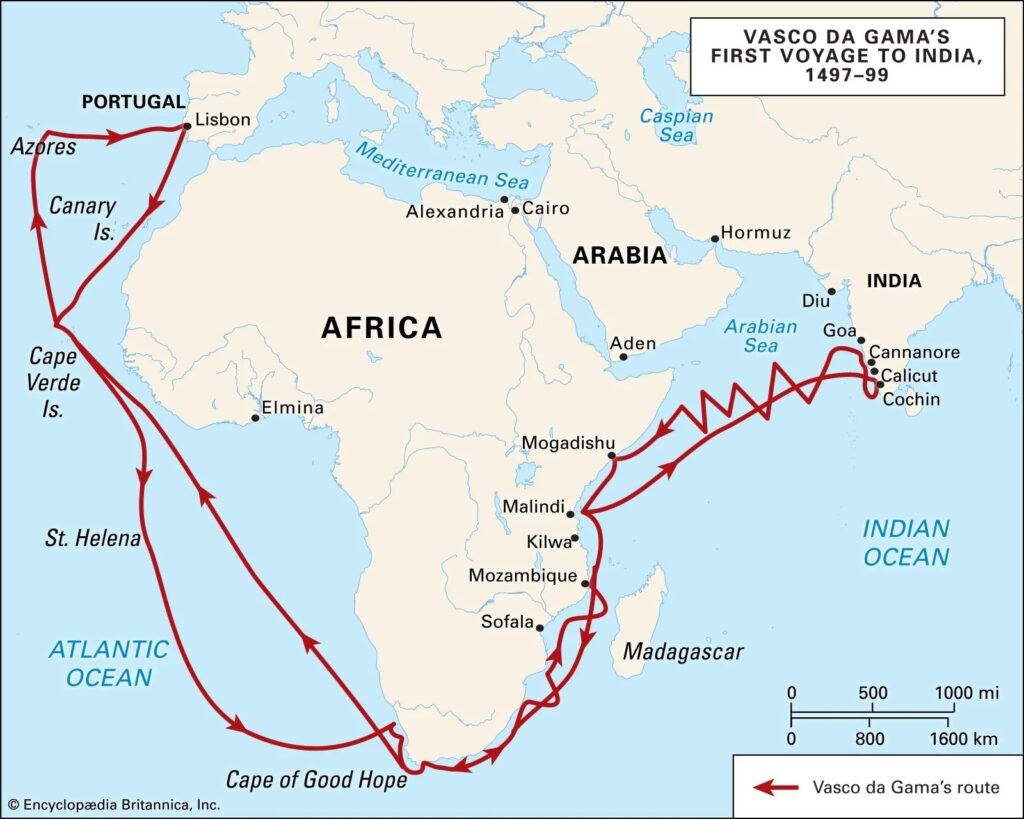

The king’s instructions to the 28-year-old captain were to round the Cape, reach India, find Christian rulers, and open new sea trade routes for the enrichment of the Crown. Vasco set sail in 1497, equipped with two new purpose-built vessels, the São Gabriel, under his own command, and the São Rafael, under the command of his younger brother, Paulo. Using pioneering navigation techniques, he found the Atlantic trade winds that would take him around the Cape, and then the prevailing winds to the east of Africa that eventually brought him to the Indian coast, where he landed at Calicut in 1498.

In India, he made contact with the King of Calicut (the Zamorin), who was intrigued to meet this stranger from a distant land. At first, the tentative exchanges went well, but the mood turned when the Zamorin – hoping for gold gifts from the emissary of the King of Portugal – instead received some cloaks, hats and a few bags of salt. Insulted, he ended the exchanges and sent Vasco back to his ships to think again. But having established that India could be reached, Vasco elected to sail back home. Few of his crew survived the long return trip, Paulo succumbing to disease on the way.

When he finally reached Lisbon, two years after his departure, Vasco was feted as a hero, and showered with rewards by a grateful Manuel, who now saw the way to conquer the spice trade, make huge profits in the process, and also outflank the realms of Islam. Vasco’s voyage had bent the arc of history, and shaped Portugal’s future direction. But, Manuel’s ambitions had no limit. What the voyage had established as possible, he now wanted to make a reality, and he wanted payback for the disdain displayed by the Zamorin. Vasco would have to go back.

His second voyage, which began in 1502, was one of conquest and crusade. This time, he went with a substantial fleet and instructions to teach the Zamorin a lesson and replace Arab control of shipping in the Indian Ocean and the Red Sea with a Portuguese monopoly.

The second coming of Vasco da Gama was an altogether more bloody and violent matter than the first voyage of exploration. On the way, he encountered the Miri, an Arabian vessel containing mostly pilgrims returning from Mecca. Vasco seized it, ripped off its rudder and took it under tow. His crew raided the ship for bounty but met with resistance. Vasco eventually set it alight, burning all the souls aboard except for those who jumped off and drowned.

News of his piracy had reached the Zamorin in Calicut before Vasco’s arrival. The result was an armed conflict between the two. Vasco sent a raiding party to shore and captured scores of the Zamorin’s soldiers. Back on board, he hanged them from the masts, so that their twitching bodies could be seen by those on shore. After this spectacle, he had their corpses cut up, loaded onto rowing boats, and dumped on the shore in front of the Zamorin and his retainers. Unable to overcome his foe, Vasco bombarded Calicut with cannon fire and fled to sea, beginning a long, sorry voyage back to Lisbon, with the king’s mission largely unaccomplished.

There was no grand party for Vasco this time and no further honours or rewards. Manuel turned his back on the brave captain who had conquered the oceans in his name just a few years before. Vasco, the instrument of terror and piracy, was shut out of court, not for his bloody violence but for his failure to make Portugal the undisputed conqueror of the Indian Ocean.

Manuel found other captains to pursue his vaulting global ambitions, with mixed results. Only after his death and the accession of King John III was Vasco rehabilitated and pressed once again into service, leading a new fleet to India in 1524. But this time, Manuel’s one-time Viceroy of India never set foot on his continent, dying during the voyage.

Vasco’s brilliant successes as an explorer and his bloody failures as a crusader demonstrated the fatal flaw in Portugal’s quest for global domination: it could only be secured over such a vast expanse of the globe by a massive commitment of money and an unlimited deployment of force – neither of which the small kingdom could sustain. Before that reality set in, one more monarch had a go at ruthless empire-building – with disastrous consequences.

James Plaskitt is a retired politician who was a member of the British Parliament from 1997 until 2010. He now lives in the Algarve.

Next month: King Sebastian