Pretty much everyone knows about the importance of bees, in particular of honey bees. They are the natural producers of honey and, more importantly, the greatest pollinators without whom many of our crops would fail, spiralling life on Earth as we know it into a chaos of food shortages and starvation. Dramatic as that may sound, it’s not far from the truth. Honey bees really are that important! Yet, despite widespread awareness of the honey bee’s essential role in the food chain, far less is known about the striped black and yellow insect itself or its colony life.

Although there are roughly 20 thousand species of bees on our planet, only a few of these are honey bees. The most common and widespread of honey bees is the Western or European honey bee (Apis mellifera). The Iberian subspecies (Apis mellifera iberiensis) can be found throughout Portugal’s countryside and even in urban areas. In the Algarve, the barrocal countryside and surrounding forests are rich in almond and orange groves, strawberry trees and eucalyptus plantations. These, alongside a vibrant mix of wildflowers, create ideal conditions for wild honey bees and apiaries to thrive.

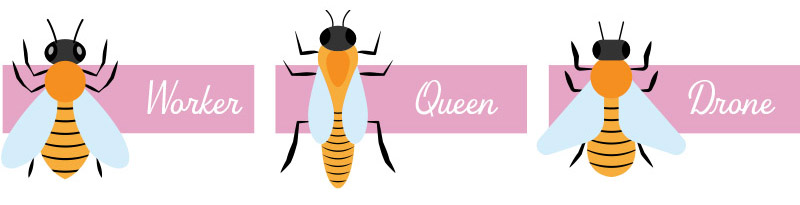

Honey bees live like a complex organism, more so than as individuals. The exception, of course, being the queen bee. In a colony, there are three types of bees which have different life cycles and roles within the community: worker bees, drones and a single queen bee.

Worker bees are the most numerous and are by far the busiest bees. A single colony can house 60 to 80 thousand bees, mainly workers.

It has been widely advertised that in its lifetime a single worker bee visits hundreds of flowers to produce a single teaspoon of honey. That might be the case, but that is not all it does. Worker bees are responsible for a great deal of what happens in a colony. Their tasks include housekeeping, foraging, defending, and even controlling the temperature inside the nest.

Worker bees are born in a single hexagonal cell where a single egg was initially laid. In this cell, it develops from egg to larva, to pupa and finally hatches from the wax-sealed cell as an adult and fully formed honey bee. Over the first weeks of their lives, their role is to attend to the cleaning and maintenance of the nest, serve the queen bee’s needs, produce wax, and protect the colony against intruders.

After a few weeks spent indoors, worker bees are ready to start venturing out and foraging. They will seek flowers and plants to extract substances such as nectar and pollen, and also look for fresh water sources to drink and gather water.

The body of a honey bee is perfectly adapted for its foraging needs. The long tongue or proboscis allows it to suck nectar, water and other liquids that they are able to store in a stomach-like gland from which they can later regurgitate when they are back at the hive. Their hind legs are shaped in such a way that they can collect pollen around the knees and transport it back to the colony.

Worker bees have also developed an amazing communication strategy to effectively report any location of interest to the other bees in a colony. Interesting sites could be a blooming field or a suitable new home. After returning from a flying trip, a bee will place itself around other flying bees and position itself at a certain angle on the wax comb and start to buzz vigorously. The angle, aligned with the sun’s position, will tell the other bees the directions they should take and the intensity of the buzzing indicates the distance. The more it buzzes, the further it is. This amazing behaviour is called a “waggle dance”.

Queen bees areunquestionably the centre of attention, without whom a colony would not succeed. Unlike ants and other insects, queen bees are not that much bigger than other bees. They have slightly longer and more slender bodies, but are hard to tell apart, especially when moving among hundreds of worker bees.

The start of a queen’s life is the same as that of a worker in the sense that it is just another egg laid in a cell. Somehow, worker bees will treat this egg differently: they will build longer walls around this cell and feed the larvae exclusively on a super-rich substance packed with proteins and other nutrients called ‘royal jelly’. This favourable treatment will mean that these larvae will develop differently and eventually result in the hatching of a new virgin queen.

When the queen hatches, she will need to fly out and mate, a process known as the nuptial flight. During this short flight, she will mate with several drones, a very effective way to diversify the gene pool. When she returns to the colony, the queen is ready to start laying fertilised eggs. During her three to five-year lifespan, she can lay over one million eggs.

Queen bees rarely leave the nest. The exceptions are the nuptial flight and when swarming.

Only one queen bee rules in each bee nest. If two queen bees happen to be in a colony at the same time, they will fight until one is dead.

Drones are male bees. Born in spring and summer, they are the Homer Simpsons of honey bees (they have one job!) and their sole purpose in life is to mate with virgin queens. They rise up to the skies and congregate in active zones where they seek queen bees on their nuptial flights. Those who are able to copulate successfully in midair detach their lower abdomen to stay with the queen bee and fall to the ground to die … job done.

Apart from this vital role for the continuation of species and diversifying the honey bees’ gene pool, drones do little more than eat and rest (again, much like Homer). As such, when the weather starts to get cold and workers “decide” that it is time to be frugal with food stores, drones are expelled from the colony and stopped from coming back in the nest, effectively starving them to death.

Together, these honey bees are all crucial to the success of a colony and for the continuation of the species. In terms of reproduction, despite the millions of eggs laid by queen bees, honey bees reproduce by splitting colonies. One strong colony can divide into two or more colonies, which will eventually split into others, and so on. A swarm of bees is precisely this: part of a colony formed by flying worker bees that, together with a queen bee, decide it’s time to make a new colony and find a new home. Behind them, they leave young worker bees, stores to keep them (such as honey and pollen), and a queen cell ready to hatch and become the new ruler.

Swarming typically occurs in springtime with the arrival of warmer temperatures and an abundance of flowering plants. In the sunny south, particularly across the Algarve region, honey bees can start to swarm as early as January. Local beekeepers watch for swarms to collect and add to their hives, thereby strengthening their apiaries. A truly symbiotic relation exists between man and bees, as man will provide appropriate housing facilities and healthcare in exchange for the natural produce: beeswax, pollen, royal jelly, propolis and, of course, the sweet honey.

Fun facts

Drones do not have a father, but they do have a grandfather! That’s right, drones are born from unfertilised eggs; therefore, they have no father. However, a queen is born to a fertilised egg meaning a queen’s father is the drone’s grandfather.

Bees have five eyes: the obvious two big eyes on each side of their face, plus three little eyes called “ocelli” on the top of their heads. While the larger eyes detect shapes, objects and distance, the smaller ocelli detect variations in light and movement.

Joke

Q: Why do bees stay inside the hive during winter?

R: Swarm!