PHOTOGRAPHY Maria Júlia Forli Telles

The Algarve, renowned for its stunning coastlines and diverse marine life, faces both opportunities and challenges as tourism continues to surge. Among its most cherished residents are the short-beaked common dolphin (Delphinus delphis) and the bottlenose dolphin (Tursiops truncatus), both of which play a vital role in the region’s ecosystem.

In July 2024, Brazilian marine biologist Maria Júlia Forli Telles was studying for her master’s degree at the University of the Algarve. Alongside Rui do Santos and Professor Rita Castilho, she conducted crucial research highlighting the impacts of tourist activities on these remarkable marine mammals.

Dolphin watching has grown exponentially over the last five decades, offering a sustainable alternative to keeping these intelligent creatures in captivity. This form of ecotourism is not without its merits. It promotes environmental education and provides vital funds for conservation efforts. However, recent studies reveal that tourist boats can significantly alter dolphin behaviors, raising concerns within the scientific community regarding the long-term impact of tourism on marine life in the Algarve.

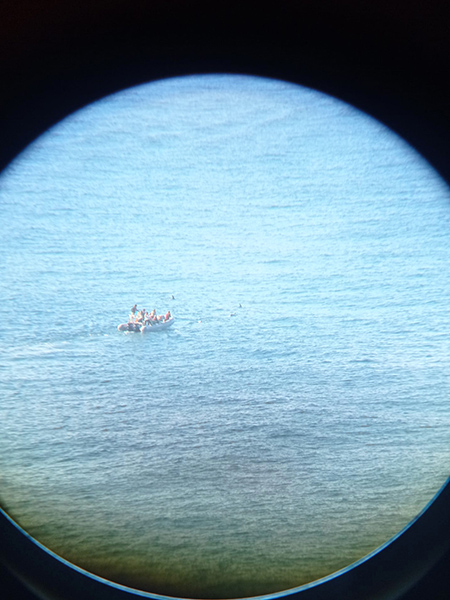

To investigate these concerns, the research employed two primary methods: observational studies from lighthouses and bioacoustic analysis of underwater dolphin communications. By leveraging the Farol project initiated by Rui do Santos in 2021, the team was granted access to several coastal lighthouses, including Farol de Santa Maria, Farol de Alfanzina and Farol do Cabo São Vicente. This observational strategy allowed researchers to monitor dolphin activities in relation to boat traffic from elevated vantage points at locations like Vilamoura and Albufeira.

The bioacoustic element of the study involved deploying hydrophones to capture the unique sounds dolphins use to communicate, such as clicks for echolocation and whistles for social interaction. These recordings were taken in both the presence and absence of tourist boats, enabling the team to analyse the impact of noise pollution on dolphin communication patterns.

The findings were illuminating. The study concluded that tourism significantly affects three critical aspects of dolphin life: feeding, breeding and sleeping. The extent of this impact varies based on factors such as group size, habitat location and local tourist density. For instance, smaller dolphin groups residing in coastal areas experienced marked behavioural changes, while larger, more mobile groups in deeper waters were less affected by tourist presence. Factors such as water pollution and diminished prey availability also further complicate the impacts that dolphins face from growing tourism.

The Algarve serves as an essential habitat for both the short-beaked common dolphin and the bottlenose dolphin, providing breeding grounds and feeding opportunities. However, the noise from boats can disrupt dolphin communication, hindering their ability to locate prey and interact with one another. Through cooperation with tourism companies, the researchers collected over 267 minutes of audio data, resulting in thousands of recorded clicks and whistles from both species.

Notably, the short-beaked common dolphin displayed significant alterations in whistle patterns in the presence of boats, characterised by shorter whistles paired with an increased frequency of vocalisations. This suggests that these dolphins are striving to communicate despite the encroaching noise pollution. Conversely, the bottlenose dolphins exhibited minimal change in their whistles but showed significant alterations in their clicks, indicating that their echolocation capabilities were more heavily impacted.

Such behavioural changes can have accumulating effects, diminishing breeding success and overall population health. To further assess the duration of these impacts, researchers utilised lighthouses as observation points, providing a less invasive method of study that also offered a broader observational reach. Alarmingly, the research indicated that at key observation sites in Albufeira and Alfanzina, dolphins were exposed to boats for approximately 39% of daylight hours, with the number of vessels frequently exceeding sustainable limits.

Yet, amid these concerning findings, there is a glimmer of hope. The willingness of tourist agencies to collaborate with researchers on such studies reflects a growing awareness and care for these marine beings. Many tourists also express a preference for environmentally conscious operators. By adopting sustainable practices that prioritise dolphin welfare, these companies not only enhance their reputation but also contribute to the conservation of the region’s marine biodiversity.

Nevertheless, creating a sustainable tourist industry in the Algarve remains a challenge. As the demand for dolphin observation grows, so does the urgency for further research and the implementation of effective conservation measures. Individual species’ characteristics must remain at the forefront of these initiatives to protect the delicate balance between tourism and marine life.

In conclusion, the work of Maria Júlia Forli Telles and her colleagues underscores the fragile intersection between tourism and conservation in the Algarve. By advocating for responsible tourism that respects the natural world, we can ensure that the enchanting dolphins of the Algarve continue to thrive for generations to come.