April 25th is a date that defines modern Portugal. Every town and village up and down the country has a road or a square called Rua 25 de Abril and the iconic suspension bridge in Lisbon bears this name. The day is a national holiday and celebrated with solemn speeches and music. What’s its significance?

On this day in 1974 a military coup overthrew a dictatorship that had lasted for well over 40 years. In order to understand these events it’s useful to appreciate the very turbulent start to the 20th century that Portugal experienced. In 1910 the centuries-long, decaying monarchy was abolished and the democratic but highly volatile First Republic established. It was short-lived as a coup d’état, in 1926, put in place a National Dictatorship, soon to be followed by the highly repressive New State (Estado Novo) in 1933, led by António Salazar. Nationalist and conservative values were imposed on the population under the motto of ‘God, Fatherland and Family’ as cornerstones. There was strict censorship and PIDE, the secret police, was ever-present to enforce adherence to the regime by repressive means. The long-lasting colonial war took its toll on a weary population and exhausted the country’s resources. The peaceful revolution of the 25th April changed the country forever.

This year Portugal is celebrating its 45th anniversary of the revolution. I’m privileged to be able to speak to people who lived through these times and who appreciate the profundity of the events.

70-year-old Teresa Boniné likens the 25th April to a bottle of champagne: “We were the people stifled inside, living in fear and isolation from the rest of the world. When the cork popped, there was a tremendous explosion of euphoria and energy. It was incredible!”

Teresa and her friend Susana Matos, 65, tell me what life was like during the dictatorship and what led to the extraordinary events they experienced in different ways. In the 1960s they were too young to understand the ideology of the political regime but were moved by the scenes at the quaysides of ships, full of young recruits, embarking for Angola. Many were to return in coffins having fought a war they did not understand. “We were told ‘Angola is ours, we have to defend it’,” Susana says. “Anyone who had brothers, male cousins or sons was utterly disheartened. I remember thinking how lucky I was not to have any brothers.”

According to the ideology of the regime, the colonies had to be retained at all costs despite the fact that other European nations had begun a gradual process of decolonisation, putting pressure on Portugal to follow suit. “We remain ‘proudly alone’ (orgulhosamente sós)” was the response of the regime, blindly pursuing the intractable colonial wars consuming 40% of the national budget and sacrificing ever more young lives.

In 1967 Teresa was in Lisbon with her fiancé. The army was in need of more ‘cannon fodder’ and began to recruit students, which also included her fiancé. There was agitation in the universities in Portugal and also awareness of the student movement in Paris at the time. Many fled before being called up, with the conscientious objectors (refratários) forming an ever-growing community in Paris.

Teresa’s fiancé was mobilised for Angola in 1969 but like some others, deserted. Teresa joined him soon after in Paris. “It was not an easy decision to make,” she explains. “I couldn’t discuss this with my family; I just had to leave, fearing I would never again return.”

Susana has a different story to tell. She was working as a teacher in a school in a small village in the eastern Algarve, near the river Guadiana. “There was very little political awareness in the village,” she says. “The textbooks we used were heavily censored and we had to follow the doctrines of the state to the letter.” She remembers the crucifix on the wall in the teaching room, flanked by a picture of Salazar.

And how did women fare at the time? Susana is eager to explain. Society was highly patriarchal and women were subordinate to men. Their role was to stay at home and look after the children. All the rights we take for granted today were denied. They couldn’t vote nor could they travel abroad without permission from their husbands. Illiteracy levels were near 70% with little access to information other than that conveyed by the church. In the countryside women also worked on the land at harvest time and in industrial areas provided part of the labour force in the factories, as men were absent because of the war. “But they were always paid less than the men,” Susana adds. “Trade unions were prohibited by the regime but the banned Communist party organised clandestine activities and raised awareness.”

68-year-old José Manuel Rosa was a serving officer in the army at the time and is able to tell me exactly what happened on the day of the revolution. He was called up in 1972 and did his military training at Escola Práctica de Infantaria in Mafra north of Lisbon, followed by officer training. Due to particular orders of despatch he was never sent to the colonies. “On the one hand we wanted to go because the sooner we went, the sooner we would be discharged. But of course, there was the fear of having to go into the war zone,” José explains. In February 1973 he entered the Caçadores 5 (Light Infantry) in Lisbon and was involved in the action on the April 25th.

Many of us already know that the revolution was peaceful and that the government was overthrown without bloodshed but how did it actually happen?

José tells me that on the evening of the April 24th, all officers received an invitation to attend a meeting. “We already knew that something was in the air but didn’t know what it was. As the officer in charge that night, I did the rounds and checked the sentinels so I was the last to arrive. When I entered the mess a fellow officer gave me the thumbs up and I knew this was it,” José says.

He shows me a letter he has kept all these years that was given to everyone at the meeting. It’s a closely typed document divided into sections with numbered points. I’m amazed to discover that this is the actual Programme of the Armed Forces Movement (Movimento das Forças Armadas, MFA) that outlines very clearly the immediate and short-term actions to be taken.

The MFA played a key role. It developed in the early 1970s as a secret movement of ‘Captains’ involved in the fighting in the colonies. Initially it was based on internal issues to do with career progression but soon took on a political dimension opposing the continuation of the colonial wars and pressing for regime change.

I’m eager for José to tell me what happened next. “Well, we waited in the mess and heard the first signal at 22.55. It was a popular song, E depois dos Adeus by Paulo Carvalho, broadcast on the radio. Only the Captains of the MFA knew the significance of this. I was told to get the soldiers ready and to issue them with weapons,” he explains.

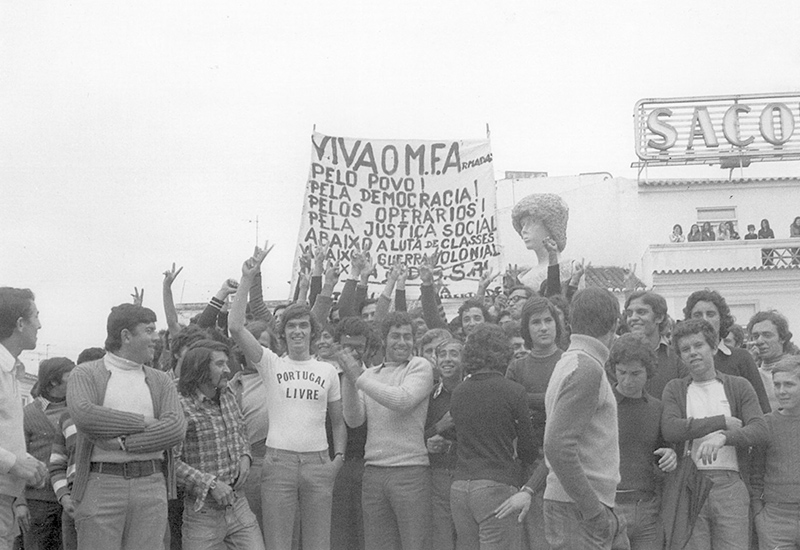

At 00.25 the banned song, Grândola, Vila Morena by the well-known protest singer Zeca Afonso was broadcast to indicate the start of operations. “We began to occupy significant positions in Lisbon as well as in other cities up north without encountering opposition,” José says. Six hours later the government fell. Despite repeated radio appeals by the MFA for people to stay indoors, the streets were flooded with thousands supporting the military insurgents. As one of the gathering points was Lisbon flower market, soldiers were given carnations. The image of the red carnations in the barrels of the guns became iconic and gave the revolution its name.

“It was overwhelming. I simply cannot begin to describe how we felt. As there was little information at this stage we didn’t really know the full picture or the consequences but it was euphoric! I didn’t sleep for five days!” José smiles.

On May 1st a huge demonstration of support took place in Lisbon with even more red carnations on display. José tells me about an incident that is still very vivid in his mind. “A woman asked me to give her a carnation that had been passed on to me. Her daughter had suffered persecution and after her arrest, fled the country.” José becomes visibly emotional and has to pause before continuing, “She wanted to send this carnation to her daughter so she could celebrate the revolution.”

But it was not plain sailing. The period afterwards known as PREC Processo Revolutionário em Curso, (On-going Revolutionary Process) was difficult, characterised by continuous political turbulence. As a result of the sudden withdrawal of the military from the overseas colonies, hundreds of thousands of so-called retornados – workers, business people and farmers of Portuguese origin – returned to Portugal, fleeing the civil wars in the now former African colonies. They had to leave everything behind, arriving on aircraft shuttles with no more than the clothes they were wearing. No doubt a hugely traumatic experience. Long-term, the retornados with their particular experiences and qualifications were able to assist in the development of a country that desperately needed to evolve.

On the April 25th 1975 the first free elections in Portugal were held and a new constitution drawn up.

Teresa and her husband were now able to return to Portugal. In 1977 they completed the university courses they’d abandoned, encountering a new world. “Youngsters were involved in fervent discussions and debates; something we had never experienced,” she says. “There were disagreements within families too, sometimes leading to disputes and even divorce. Perhaps something inevitable in this situation.”

Susana’s reactions are similar: “When we heard about the revolution of the April 25th in our village, the initial reaction was actually fear. We could listen to the radio but there were few televisions and the impact didn’t hit us at first,” she says. Gradually people began to organise to improve things in the village. For the first time women were an integral part of developments. “I helped to form the first teachers’ association and I remember how we talked and talked – without fear of persecution,” she remembers.

All three agree that what they had experienced at this time was something unique, taking place at a historical juncture without equal. Since then Portugal has suffered economic crises and there are still fundamental issues to be resolved but civil rights and political freedoms have been achieved along with increased economic prosperity.

On the April 25th this year the song Grândola, Vila Morena will again be broadcast by loudspeakers up and down the country and speeches will be made in commemoration of the momentous events. As the champagne bottle has been truly popped, perhaps we should raise a glass in celebration?

This article was originaly posted in the April 2019 edition.

On the video you can listen to the song ‘Grandôla, Vila Morena’ by Zeca Afonso that was broadcasted on the radio as a signal to indicate the start of operations (with subtitles):