The way Portugal polices its borders and documents its residents is undergoing radical change. Behind the controversy about what is happening and the concern about its effects lies one man’s tragic story.

Words James Plaskitt

Ihor Homenyuk was 42 and struggling to make enough money in his native Ukraine to support his young family. So, like many before him, he made the decision to fly to Portugal in the hope of securing a better job with better pay. In March 2020, he boarded a flight to Lisbon. On arrival, he presented his documentation to the SEF border officials. They noted that he was travelling on a tourist visa. However, officials suspected that his true motive was to find work, and so he was detained and taken to the immigration holding centre of Lisbon airport.

Two days later, Ihor lay dead, face down on the floor of his cell with his hands and feet bound. For days, nobody was informed of his death. Eventually, SEF officials said that he had suffered a heart attack. The coroner investigated and declared that such a scenario was impossible. In fact, Ihor had several broken ribs and died as a result of being beaten repeatedly with a baton. In May 2021, three SEF border guards appeared in court and were found guilty of causing death by aggravated assault. They were handed long prison sentences. Ihor’s family were given compensation.

But Ihor’s tragic story was to have a longer legacy. After years of concern about the culture and conduct of parts of the Foreign and Border Service (SEF), the government decided to act. The decision was made to disband it. Questions about the organisation had been mounting for years. In the same year that Ihor met his brutal end in the Lisbon detention centre, the EU had found Portugal to be infringing the Asylum Procedures Directive. And the UN Human Rights Commission had expressed concern about “excessive use of force, including torture and ill-treatment by law-enforcement officials.” There is no doubt that SEF ran a forceful security system. The figures show that in 2020 Portugal received just over 1000 asylum requests; almost all from African nationals – 753 were rejected.

The government now felt impelled to take action. Despite a lot of opposition, they announced that SEF was beyond reform – it simply had to be disbanded and its various functions handed over to other authorities. Like so many things, progress with the move was delayed by COVID. After that, it was the general election, but last month the government confirmed that the change was finally going ahead and that May would be the last operational month for the SEF.

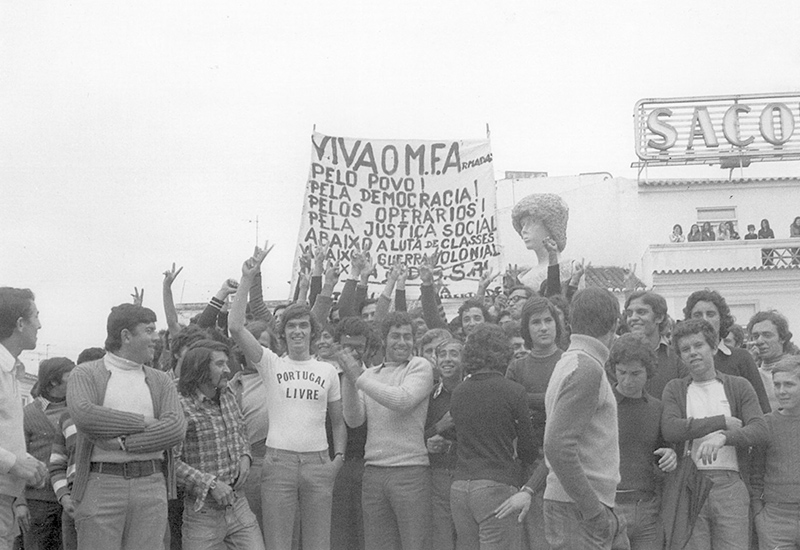

The government’s central argument is that the administration of immigration policy and the policing of the borders need to be separate and distinct entities – not wrapped up in one autonomous body like the SEF. In fact, this goes back to the original post-revolution arrangements for border security, when administration was carried out by the Border Service, and border policing was conducted by the Fiscal Guard. But the functions were merged in 1986 with the creation of the SEF, which then gradually acquired more policing powers.

The government is parcelling out the functions of the former SEF as follows:

- the administration of the asylum and immigration system will move to a new body, the Aliens and Asylum Service (SEA)

- the issuing of passports and residency documents will transfer to the Institute of Registries and Notaries (IRN)

- the inspection of maritime and land borders will move to the Republican Guard (GNR)

- the inspection of airport and cruise frontiers and the responsibility for the expulsion of illegal migrants will move to the Public Security Police (PSP)

- the investigation of illegal migration and trafficking will be undertaken by the Judicial Police (PJ)

As with almost any reorganisation of government services, the changes are proving controversial. In the last twelve months of its existence, over 200 of SEF’s 1800 staff left as a result of job insecurity, resulting in an inevitable tailing off in performance. Unions have had several rounds of meetings with the government attempting to secure transfer packages and job protection, but progress has been slow. Opposition parties in the Assembly have urged postponement of the changes as uprooting all existing arrangements in the middle of the Ukrainian refugee flow is not ideal. And, as many ex-pats await the move from their old residency documentation to the new biometric cards, now may not be the best time to transfer the responsibility for an already delayed and troubled process.

There is also concern that many of the bodies about to assume new responsibilities are not fully prepared. Training has only just begun for officials who are about to take over new responsibilities within the following weeks.

But, ready or not, the changes are already underway. As is often the case in these circumstances, there may turn out to be something of a gap between the political imperative to do something and the finesse with which the something is actually done. The disaggregation of functions can undoubtedly avoid the excesses of overbearing power and diminished accountability – but it always comes with the risk of being replaced by that unmistakable background noise – of a buck being passed.

James Plaskitt was a member of Parliament in Tony Blair’s government in the UK. He is now retired in the Algarve.